- May 9, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

This story is a portrait of an artist. The late John Sims is the artist in question. What kind of artist? Well, that’s a tough question. Like Walt Whitman, Sims was large. And contained multitudes.

This artist was a true polymath. Sims’ creations covered the multimedia map. He expressed himself via spoken word poetry, digital art, music, video game creation, installations, conceptual art and clever pranks.

Sims’ obsessions included mathematics, racial justice, the codes of national and tribal symbols (i.e., flags), and political action and Pi — the most irrational number of all. This artist had a lot to say. And he said it in many different ways.

But Sims also liked to give others a voice.

Artistic collaboration was Sims’ style. And not just with other creative individuals. His projects brought groups of people together across cultural ethnic and political divides. Bringing people together has its risks. Failed attempts lead to fights, feuds and factions. Sims didn’t flinch and kept trying. Risk-taking was also his style.

You can see Sims' work at a retrospective, "From the Chambers: Honoring John Sims" at The John and Mable Ringling Museum. It's on display until Aug. 6.

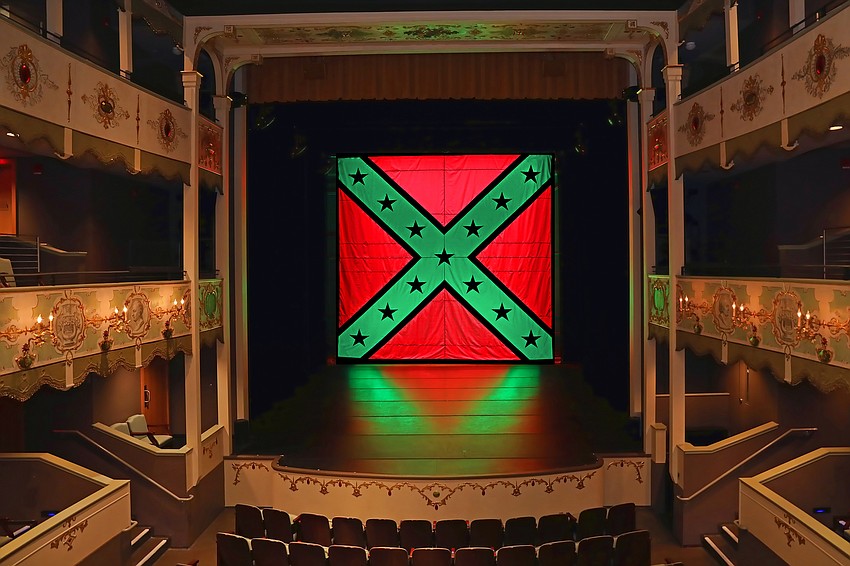

Sims' recent conceptual art series buried and lynched Confederate flags. That infuriated white supremacists. That’s definitely a risk. They’ve got more guns and ammo than many third world countries. And plenty of hate.

But Sims had plenty of love. His big heart drove his connections with communities and individual creators in his world — and sometimes the next. Sims honored the artists who came before. His final artistic creation honored one in particular.

For nearly a decade, Sims lived a few blocks away from me in downtown Sarasota. My house was on 14th Street; his home/studio was on 10th Street, which was on my way home.

Every few days, I’d see him on the sidewalk. I’d drive by; we’d wave at each other. That two-second connection was pretty much it. What a waste. I could have easily popped into Sims’ studio all the time. I rarely did. But Sims wasn’t the only artist in the neighborhood.

Sculptor John Chamberlain also had a 10th Street studio. He was an Abstract Expressionist who worked in the medium of salvaged auto parts. Chamberlain bent, folded and mutilated that junk, fused it together, then splashed the result with candy-colored paint. I couldn’t visit this artist because he’d moved to the next world. But I talked to him once.

I interviewed Chamberlain in the mid-1990s. He quickly turned it around and interviewed me. I stubbornly worked my list of questions. He kept going off-script. Our chat became a verbal chess game. And Chamberlain was a verbal chess master. As I recall, he was smart, cagey, guarded, profane, hilarious, unpredictable and always one move ahead. It was one of my best interviews ever.

Chamberlain left town in 1996, and left this world in 2011. His 10th Street studio stayed in place for years. A hulk. A shell. A memento mori. Eighteen thousand square feet of pure waste.

That 10th Street ruin was also on my way back home. I’d pass it after waving to Sims, but rarely looked. The building had been part of my landscape since childhood. I took it for granted. Sims didn’t.

Like most true artists, Sims was an ancestor worshipper. Even if you’re only halfway good, you know you stand on the shoulders of giants. You also know the debt you owe these giants. Nothing less than the techniques in your hands and ideas in your head.

There are only two ways to pay the giants back. Remember their names. Make sure others do. And make damn sure nobody tosses their art and legacy in a dumpster.

That’s not just a metaphor. I found that out last September.

I was driving by the site of Chamberlain’s studio. It was missing from the landscape. No studio. Only a gutted shell remained, but not for long. Cranes were ripping through the wreckage like giant carrion birds. I parked my car, got out and took an iPhone video. I sent it to Sims, then called him.

“Hey John. They’re demolishing …”

“John Chamberlain’s studio. Yeah, I know, Marty. I saw it.”

“You don’t sound surprised.”

He wasn’t. A few weeks back, Sims had read the city’s demolition order posted outside the studio. He’d come back to with a digital video camera. Not just once. Sims documented the destruction every step of the way.

“What’ll you do with the video?”

“I don’t know yet. But I will do something. And I’ll still be going back …”

Sims' video was better than mine.

He did do something.

To quote Sims’ essay in “Sculpture” magazine:

“I pour some coffee libation to the ground in memory, in honor and respect for the spaces that bring forth the best evidence of our humanity and capacity to create. Now, I am ready to get to the studio and work on my newest piece.”

The “piece” Sims refers to is a liberated (and transformed) shard of disrespected art history. A work of art, but not conceptual art. It’s a physical object. And heavy as hell.

Sims did go back to Chamberlain’s gutted studio. That’s where he found that shard. A rusty metal spike painted a happy shade of chrome yellow.

Sims pulled that spike from the ruin. Now what?

The junk was too big for his car. His studio was 1,056 yards away. There was only one way to get it there. Artists sometimes suffer for their art, right? This was one of those times.

Sims dragged that heavy metal down 10th street up to his own studio. Then got to work hammering it into the shape of a spike crowned by an infinity symbol — and magically turned junk into sculpture. Sims named it “From the Chambers.” It would be his final artistic creation.

Sims died on December 11, 2022. So it goes.

You can see his tribute to John Chamberlain at the exhibition that shares the sculpture’s name. Steven High curated this show. It’s minimalistic and stripped down. And it hits you like a slap to the face.

Sims’ sculpture stands on one side of the gallery. Chamberlain’s sculpture hangs on the opposite wall. The two pieces initially seem to reflect each other. But they’re radically different.

Sims’ “From the Chambers” (2022) looks like 3D steel calligraphy. A punk rock glyph, with a rough, raw texture. Chamberlain’s “Added Pleasure” (1975-1982) is painted and chromium-plated steel. Slick and shiny.

Sims’ sculpture is a Chamberlain homage, not an imitation. It’s made of banged-up metal, sure. But that’s its only resemblance.

The two artworks aren’t mirror images.

They face each other. But they’re not reflections.

They’re looking each other in the eye. And having a dialogue.

Sims’ art always sparked dialogue. It’s seems he’s done it one more time.

In an adjoining gallery, Sims’ video documentary plays in an endless loop. The giant carrion cranes erase history, again and again. His poem also plays from a speaker on the ceiling. Sims’ words, Sims’ voice. Half manifesto. Half mournful elegy.

“No man is an island.” John Donne said it. John Sims knew it.

My continent of self is a little smaller now that Sims is gone. Along with John Chamberlain, Kevin Dean, Allyn Gallup and so many others.

Nothing lasts forever. That applies to both buildings and people. Including the smart, creative artistic ones who make our world a little better.