- May 3, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

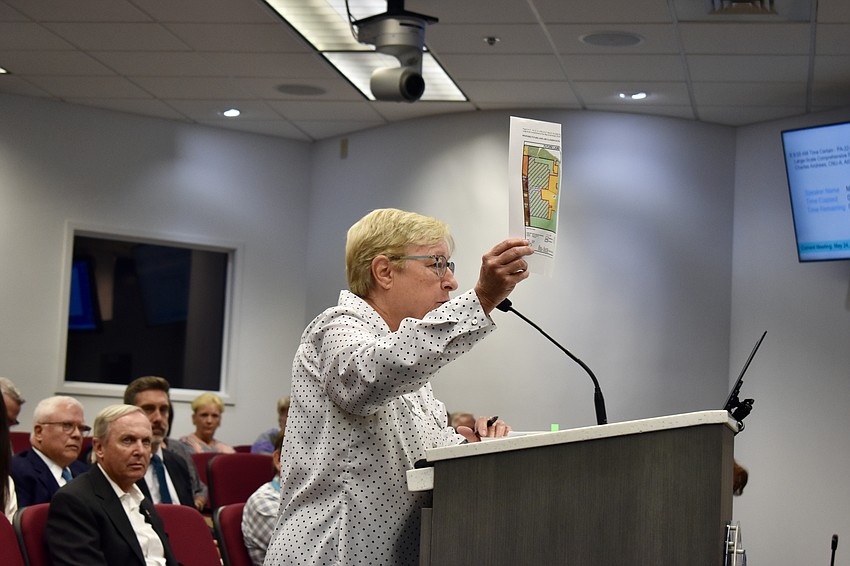

Bradenton Attorney Patricia Petruff has represented developers for decades, and thus is very familiar with their wants and needs.

But one thing, she said, they don’t need is Senate Bill 540.

The new law, which went into effect July 1, could make challenging proposed development more expensive.

That could be key in Manatee County, where tremendous growth has led to what many residents claim is unchecked growth.

SB 540 has been dubbed the “Sprawl Bill” by environmental groups after it was signed into law by Gov. Ron DeSantis.

Basically, if a citizen or group loses a lawsuit against a developer, builder, business or municipality trying to stop a project, the new law allows the winning side to be compensated for all legal fees it had to pay to defend itself in court.

While that could either help or hinder either side, Petruff said citizens or small interest groups seldom have the funds to challenge big business.

“Nobody — not any of these little local opposition groups — can afford to pay those (legal) fees,” Petruff said. “It could be upwards of $30,000 to $75,000. It’s bad for the citizen who bought (a home) in a rural neighborhood and depended on the (Future Development Area) boundary being there until 2035 or whenever it was supposed to be there still. It’s way different than the person who moved in next to Tropicana and doesn’t understand that during a certain time of the year, they burn orange peels and it smells funny.”

Petruff was hired to represent the East Manatee Preservation, a group formed by concerned citizens, in a move to halt Carlos Beruff’s East River Ranch development that lies east of Manatee County’s Future Development Area Boundary. That area was supposed to be protected from higher density projects.

“I don’t have a problem with development,” Petruff said. “If you look at my record, I have represented developers my entire legal career. I’ve been here for 43 years, so it’s not like I’m insensitive to what developers want and need. (SB 540) is very draconian and will have a chilling effect on citizens exercising their right to disagree with the government. It’s going to be pushing a big rock up a really steep hill in my opinion.”

She expects to see far fewer challenges to development projects across the state as a result. The threat of a lawsuit by a citizen or a group has lessened the checks and balances of uncontrolled growth.

How the new law will effect municipalities has yet to be determined. Like big business, municipalities often have the funds to deal with court issues.

The county, for instance, could benefit if it approves a project and is sued by a citizen or group with the claim the project doesn’t fit the comprehensive plan or the project is not compatible with the neighborhood. If the county then wins such a case, it could be reimbursed for court costs it had to pay to defend itself.

However, if a county commission denies a project, and later is sued by a builder and loses in court, it will have to pay legal fees incurred by both sides.

District 5 Commissioner Vanessa Baugh said commissioners feel pressure not to oppose development projects because it has become likely that such a decision often is met with a lawsuit. She said recent history has shown the courts have favored development and it has made it likely the county — and ultimately the tax paying residents — will be on the hook for court fees. Now, with the new law, commissioners have to consider they could be subjecting the county to even more court fees.

“It basically takes away power from the counties,” she said of the new law. “Each county has a different comprehensive plan, and that’s part of the Board of County Commissioners’ job (to decide whether projects meet criteria specified in comprehensive plans).”

But will a judge agree?

Even prior to the bill passing, Baugh had expressed frustration over the board ending up in a no-win situations, such as when the county lost a lawsuit to Tara developer Lake Lincoln.

If it agreed with Tara residents that the commercial development should not be allowed, it would be sued by Lake Lincoln. If it allowed the project, it was likely to be sued by the residents.

Eventually, the board sided with the residents, and 11 years of litigation with Lake Lincoln followed.

“It’s bizarre because we had it in writing from Lake Lincoln that it was never going to build commercial property on that property,” Baugh said. “Yet, they turned around and sued, and they won after 10 years.”

If this case began today, with the county defending its decision to decline the commercial development, and Lake Lincoln won the lawsuit, Manatee County could have to pay Lake Lincoln’s legal bills. In the actual case, the two sides eventually settled with Lake Lincoln receiving $3.6 million in exchange for the parcel. But the county can absorb such costs. Can a special interest group or an individual?

Consider a nonprofit group or individual trying to pick up the tab.

The concern is that developers with deep pockets now have free rein to “sprawl.”

Lawmakers tried to temper SB 540 with an added bill that required the prevailing party to prove the challenge was frivolous before the winning side would be entitled to legal fees. That bill failed.

In a case brought against Manatee County before the bill became law, Save Gates Creek and its Neighborhoods Inc. sued Manatee County after the board voted to amend its Comprehensive Plan to allow Cox to build a car dealership off State Road 64. Attorneys for Cox filed a “motion to intervene” based on the Florida Rule of Civil Procedure that “anyone claiming an interest in pending litigation may at any time be permitted to assert a right by intervention.” It joined Manatee County in the lawsuit.

When Save Gates Creek lost the lawsuit, Cox and Manatee County attorneys would have to pursue ways to recoup their court costs. If this case was filed now, the new law would have required Save Gates Creek to pay the legal fees of Manatee County and Cox, plus “reasonable” appellate attorney fees and costs.

Florida Sen. Nick DiCeglie, a Republican from Pinellas County, sponsored the bill. DiCeglie told the Senate Rules Committee that citizens need to put “more skin in the game” when challenging comprehensive plans.

Cox Chevrolet was approved to build the dealership in October 2020. After two plus years of legal filings and accumulating attorney fees, Cox remains approved to build the dealership. However, the groundbreaking for the project has been delayed.

Baugh voted against the dealership because, in her opinion, it was not compatible for the neighborhood. However, the project ultimately was approved 4-3. When such decisions are so hotly contested in Commission chambers, the likelihood of a chalenge in court rises. But with SB 540, that might no longer be the case.

Population numbers point to more development in East County. In December 2022, the United States Census Bureau released findings that Florida grew 1.9% from 2021 to 2022 reaching a population of 22,244,823 residents.

“For the third most populous state to also be the fastest growing is notable because it requires significant population gains,” the report read.