- April 4, 2025

-

-

Loading

Fifty-five.

That's the number of oil portraits that Beck Lane plans to paint of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo.

Why 55? That's the number of self-portraits that Kahlo created during her 47-year lifetime.

With prominent eyebrows and facial hair above her lip, her face framed by braids pinned to the top of her head and attired in her signature peasant grab, Kahlo would become one of the world's most recognizable female artists. (Photographer Georgia O'Keeffe is also a contender.)

Along with Our Lady of Guadalupe, Kahlo is an icon of Mexico. Her likeness adorns everything from tote bags to T-shirts to a new line of shoes from Tom's, the do-good footwear company.

"I'm not painting her because she's famous," volunteers Sarasota artist Lane in an interview at Starbuck's on Fruitville Road.

Lane made time for coffee after holding a painting demonstration in the art gallery at the Unitarian Universalist Church of Sarasota, where some of the Frida paintings are on display until Aug. 18.

Lane said she chose Kahlo as a subject for her latest portrait series because she uses photographs to paint and likes those taken from 1850 to 1950. According to Lane, there are 5,000 photographs of Kahlo in the public domain, providing no shortage of inspiration.

Lane is a native of Cape Cod who came to Sarasota seven years ago; Kahlo died in the Mexico City house ("Casa Azul") where she was born. But the two artists have something in common.

After being impaled by a pole in a bus accident in 1925, Kahlo was confined to her bed as she underwent many surgeries. To pass the time, she began painting with the aid of a lap easel and an overhead mirror in the canopy of her bed.

Like Kahlo, Lane committed herself to art while bed-ridden.

After graduating high school, Lane studied art at the now defunct Vesper George School of Art in Boston. She dropped out to work as a florist and in retail, which required heavy lifting. After her tendons tore away from her elbows, Lane had multiple surgeries to regain use of her limbs.

For both Kahlo and Lane, painting wasn't merely a means of self-expression during convalescence; the act represented the determination to survive.

“I used to paint like this,” Lane says, holding a straw in the crook of her elbow to mimic how she inserted her brush into her braces because she couldn’t move her fingers. “I couldn’t do it for very long, maybe 15 seconds at a time. I had to plan how I was going to do it,” she says.

Like many female artists, Kahlo and Lane weren't taken seriously. During her lifetime, Kahlo painted primarily for her own satisfaction and for the enjoyment of her family and friends. In the public eye, her personal, self-referential art was eclipsed by the giant murals with political themes painted by her husband Diego Rivera, who was 20 years older.

Kahlo didn't become a global sensation until decades after her death in 1954. Her fame gained momentum following the release of Hayden Herrera's 1983 biography about Kahlo. A 2002 Hollywood movie starring Salma Hayek brought Fridamania into full bloom. In 2021, Kahlo's painting, "Diego and I," set a record for a Latin American artist when it sold for $34.9 million at Sotheby's.

For her part, Lane knew she wanted to be an artist when she was a child. "One of my earliest memories is of drawing a seagull and telling my mother I was going to be an artist," she recalls.

While she was clear on her career path, Lane didn't take herself or other women artists seriously for a long time. She bought into the misogynistic stereotypes that dominated the art world. "I didn't think much of women artists," she says. "I thought they were second-class."

Still, the art scene of New York City beckoned. Artists like Keith Haring, Kenny Scharf and Jean-Michel Basquiat had taken their art to the streets and factory lofts, following in the footsteps of pop art pioneer Andy Warhol. Lane moved to the "City" when she was 48.

Lane exhibited her work in two solo shows in New York City and sold her paintings to far-flung collectors, thanks to a contract with an international gallery. But it wasn't until she was injured that she made a vow to herself to become a full-time artist.

She's had some help on her journey. Lane's sister, Melissa Voigt, senior development officer for the Sarasota Opera, helps write press releases and get the word out about Lane's art on social media platforms.

In a town filled with professional artists, Lane understands the importance of connecting with potential buyers in person. A self-described hermit who likes to walk at night when everyone else is home, Lane does emerge from seclusion to attend events at Art Ovation hotel and pop-up shows.

She lives simply, riding a newly acquired scooter she has dubbed "Speed Racer" from her live/work space near Stickney Point to and from downtown.

Mostly, she paints. "My purpose is painting," Lane declares.

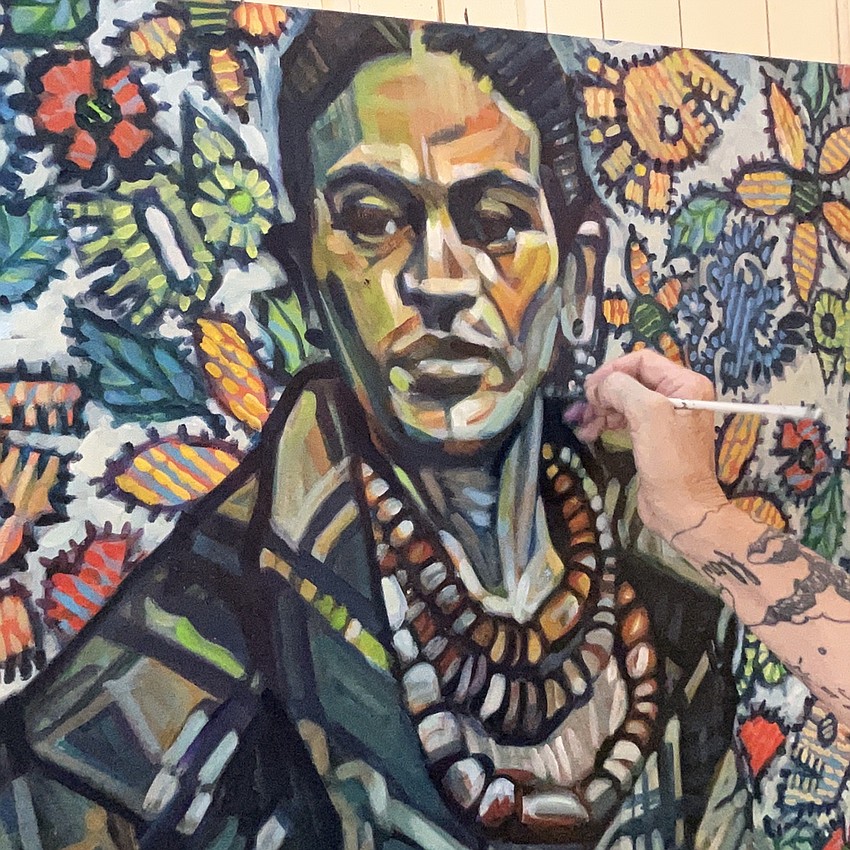

Right now, Lane's working on No. 19 of her Frida project, which she began in December. The canvases are mosaic-like, with bold brush strokes of color forming images of Kahlo in various poses, some of them gender-bending.

Lane's excited because one of her Fridas may have found a buyer in Mexico. "Wouldn't it be great if Frida got to go home?" Lane says.

In Florida, Lane's work is on display at Chasen Galleries in Sarasota and blu Egg Interiors in Fort Lauderdale. You can also find videos of Lane painting on YouTube and other social media outlets.

While Frida is her passion right now, Lane is also fascinated with another female artist, 94-year-old Yayoi Kusama. A native of Japan, Kusama dyes her hair (or wears a wig) of flaming red-orange and creates multimedia works, including sculpture, painting, installation and performance.

Having packed up the Fridas she was working on for the painting demonstration in the back of a friend's car, Lane pulls out her cellphone to reveal photos of her paintings of Kusama, including one of the artist as a child.

"She's the jewel of Japan," Lane exults, noting her goal is to have one of her Kusama portraits hanging in the Kusama Museum in Tokyo.

After years of tempering her expectations, Lane is thinking big. What about a Frida exhibit in Mexico or Santa Fe, ground zero in the U.S. for Fridamania?

Told that Santa Fe has more than 200 art galleries, many of them on Canyon Road, she pulls out a notebook and pen from her backpack. "Is that spelled C-A-N-Y-O-N Road?" Lane asks before jumping on her scooter.

Then she heads down Fruitville Road toward her studio, where more Fridas are moving from the realm of Lane's imagination to the canvas.