- May 1, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

While seizing the opportunity to create thriving, and unique, communities in Sarasota and Lakewood Ranch took the proverbial village, select individuals provided the vision to launch that effort.

Frontier Florida was not for the faint of heart, so much so that some of the Scottish settlers who arrived here in the 1800s decided the place wasn't for them and returned to their homeland.

But the area's trailblazers didn't.

These three individuals helped build our region into what it is today, building the framework, and providing opportunities, for those who followed. They made tangible, lasting changes in their environment and inspired others to do the same.

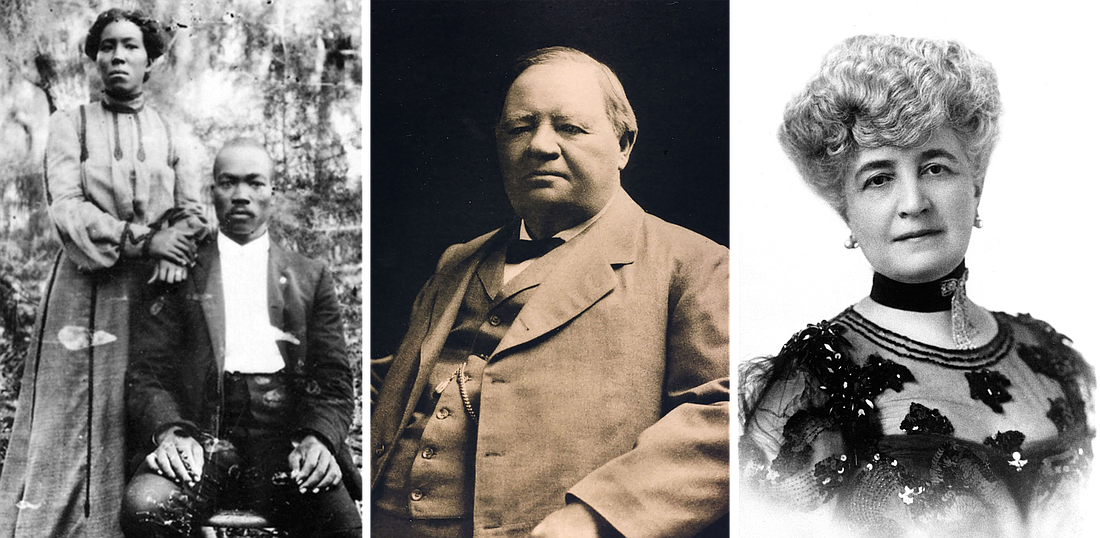

Lewis Colson, who was formerly enslaved, arrived in Sarasota in 1884 and helped map out the city. He became a spiritual leader in the Black community.

Is he well known today for his exploits? Perhaps not.

A couple deep in conversation on a bench at Selby Five Points Park probably don't realize they owe Colson a debt of gratitude, and the same can be said of the man coming out of the Selby Library, or the woman buying a ticket at the Sarasota Opera House, who might never have heard of Colson.

If these Sarasota denizens notice the historical marker in the park at One Central Avenue and take the time to read it, they will learn that Colson worked as an assistant to engineer Richard E. Paulson of the Florida Mortgage and Investment Co.

In 1885, Colson, who was born in 1844, drove the stake into the ground at Five Points, which became the center of he city that grew from from a fishing village.

There were many firsts in the life of Colson. He was the first Black man to register to vote in Manatee County. He became a minister, and he and his wife, Irene, a midwife, founded the first Black church in Sarasota.

Colson was the first minister of the Bethlehem Baptist Church, where he served from 1899 to 1915. The church was originally located at Seventh Street and Central Avenue in the Overtown neighborhood (now the Rosemary District) and remained there until 1973, when a new church was built at 1680 18th St.

In 1925, the first hotel in Sarasota for Black people, who were not allowed to stay in other hotels because of laws mandating segregation, was constructed. It was named the Colson Hotel and had 25 rooms.

The Florida land boom from 1924-1926 created work and attracted many to the area.

"Sarasota was a growing community, and African Americans were learning about job opportunities," said Vickie Oldham, president and CEO of the Sarasota African American Cultural Coalition Inc. Oldham was interviewed about Colson for the WEDU PBS documentary, "The Sarasota Experience."

Newtown Alive notes that as a midwife, Irene Colson held a respected position in the community because Black residents were denied access to mainstream medical care. The Colsons had four children — John Hamilton, James, David and Ida.

The days of being first didn't end for Colson when his life ended in 1922. He and Irene were the first and only Black residents buried in the historic Rosemary Cemetery, which was owned by his former employer, the Florida Mortgage and Investment Co.

According to Newtown Alive, the name on the Colson gravestone is misspelled as "Calson." Legend has it that the Colsons were buried during the night to avoid discontent from the families of the others buried at the cemetery, who were all white.

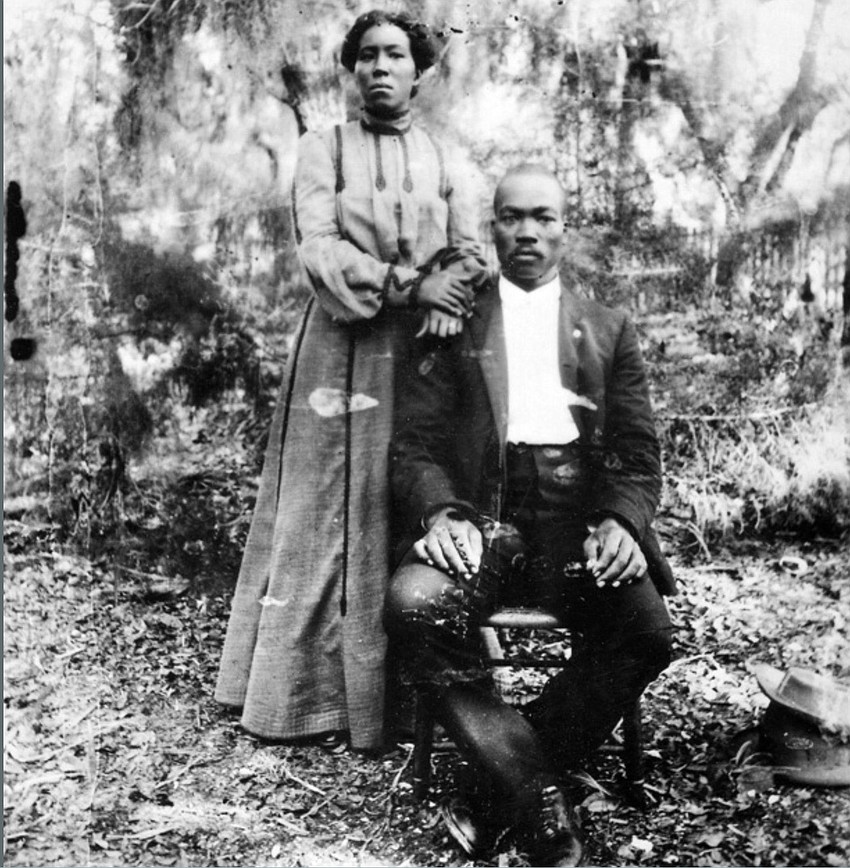

John Schroeder is not a household name. But at one time the German immigrant, who arrived in Milwaukee, Wisconsin in 1846, ran one of the largest lumber companies in the U.S.

In 1905, Schroeder bought a 45-acre property that eventually spawned Lakewood Ranch. Schroeder was attracted to Florida for its timber, but the friends he sold his land to viewed it as a vacationland.

To keep his Wisconsin lumber mills humming, Schroeder needed to chop a lot of wood. To find it, he went to places like Minnesota and Florida. In 1905, he put together a company called Schroeder-Manatee Ranch, which is the parent company of today's planned community Lakewood Ranch.

He began buying parcels of land, eventually assembling a 48-square-mile tract that eventually became known as Lakewood Ranch. After his death, his three sons continued to run the company that bore his name. They decided to diversify into furniture and even started a kiddie line called Playskool. That brand would become a household name under someone else's ownership.

But things didn't work out for the Schroeders in the furniture business. They needed money, and they needed it fast. Their friends, the Uihleins, bailed them out by buying their land in 1922 for as little as $2 per acre.

But friends being friends, the Uihleins kept the name Schroeder-Manatee Ranch Co., or SMR, for short.

For nearly 70 years after the Uihleins took control, agriculture was the focus. Timber, vegetable and citrus farming and ranching went on unabated, but these activities weren't always profitable. No matter. The Uihleins used their Florida land primarily for recreation.

In the 1980s, however, SMR began taking the first steps toward building a major planned community, and that included holding discussions with Manatee County Commissioners. As generally happens in development, not everyone was in agreement about where building should take place.

It would take until 1994 for SMR to gain the consensus and regulatory approvals needed to create its first neighborhood, Summerfield. Slowly, the community began to take shape with the addition of homes, corporate offices, country clubs, a business and entertainment hub, a post office, a hospital, a sports complex and a polo club.

A lot of the credit for SMR's transition into real estate development goes to the company's past two presidents — John Clarke, who retired in 2002, and to Rex Jensen, who currently holds the title of CEO.

Lakewood Ranch, which today straddles Manatee and Sarasota counties, has a population of about 63,000 residents in 33 residential villages. It has an average home price of $741,000 and is considered the No. 1 planned community in the U.S.

Chicago socialite and Florida land developer Bertha Palmer hasn't been seen in the Sarasota area since 1918, but her presence is felt everywhere more than a century after her death.

Palmer arrived in Sarasota in 1910 and immediately saw the potential to develop land and revolutionize agriculture. History remembers her as the wife of wealthy Chicago developer Potter Palmer. But she carved out a new life for herself in Florida as a businesswoman.

The community of Palmer Ranch bears her name. Many of the streets she named are unchanged — Honoré (her maiden name and the name of her first son), Lockwood Ridge, Tuttle, Webber and Macintosh.

Who was this formidable woman? She was born in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1849 and married a man more than 20 years older than herself. Palmer and her husband owned Chicago's famous Palmer House Hotel, which still exists today in The Loop. The legendary Chicago department store Marshall Field was originally founded by a consortium led by Bertha's husband.

After the Chicago Fire of 1871 wiped out the newly opened Palmer House, she helped support her husband and other civic leaders as they worked to rebuild the city.

When the widowed Palmer and her entourage arrived in Sarasota on a luxurious Pullman train car in February 1910, the city's only hotel was so humble that a newly opened sanitarium was quickly commandeered to accommodate the party.

It wasn't long before Palmer bought more than 80,000 acres in and around Sarasota.

Palmer proved herself an able steward of the land. She is credited with rolling out innovations that improved the Florida ranching, citrus, dairy and farming industries before she died in 1918. She was no stranger to how draining land could create development potential. It was what her husband and his business partners did to pave the way for Lakeshore Drive and the Gold Coast of Chicago.

Such was Palmer's influence that other well-heeled Midwesterners followed her lead. One of them was Owen Burns, who gave Burns Court and today's popular restaurant Owen's Fish Camp their names.

Burns was no small-time investor. He bought the holdings of the Florida Mortgage and Investment Co. from Sarasota pioneer John H. Gillespie for $35,000, gaining ownership of would be 75% of today’s city limits, according to historian Jeff LaHurd.

"Give the Lady What She Wants," was the axiom coined by Marshall Field. In the case of Bertha Palmer, the lady gave Sarasota what she wanted — her idea of civilization.