- April 14, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

Nothing is likely to assuage the families whose loved ones died from COVID at Sarasota Memorial Hospital during the pandemic.

Their experience of being unable to hug their dying loved ones will be etched in their minds — a pain that will never heal.

But as heart-wrenching as that is, if you dispassionately read all 82 pages of the three-year review of SMH’s “Response to COVID-19 Pandemic” and, equally important, remember the context of the time and put yourself in the shoes of the people on the daily frontlines of the pandemic, you can justifiably conclude:

All things considered, overall, the entire SMH staff did an extraordinary job in a crisis.

As a $1 billion enterprise in the business of curing the sick and saving lives, SMH’s staff — the CEO and its 9,000 other staff members — should be congratulated and, yes, thanked. Their three-year, day-to-day handling of this deadly epidemic showed that the citizens of this region should have great confidence in their public hospital.

Now, that, of course, is not the view of a vocal minority that has been excoriating the hospital, its board and physicians on TikTok. Sure, they did things they probably wish they didn’t or wish they had done better. And the raw nerve that continues to sting family members who lost loved ones is how the SMH medical staff and hospital treated them.

But to vilify the hospital, its management and doctors is to ignore the context; to be ignorantly judgmental; to fail to walk in others’ shoes; and to forget this most basic human trait: In times of crisis and chaos, when conditions are changing by the minute and hour, when information is unknown and changing just as rapidly, men and women rise up in the moment and take action for the good. With all they have and know, they make the best decisions they can and do the best they can.

That is the picture that emerges from the three-year review of how Sarasota Memorial handled COVID-19. SMH’s entire staff did its best. And it did well. When measured independently, SMH outperformed its peers on many levels.

Perhaps the most repeated takeaway from the three-year review will be the conclusion of Premier Inc., a leading healthcare consultant and analytics firm. In its analysis of 1,300 hospitals, Sarasota Memorial’s COVID mortality rates were better than those of Premier’s national, South Atlantic, Florida and peer hospital benchmarks.

Premier reported that if all hospitals in its analysis had the same mortality rate as SMH (5.6% versus 14.4% for hospitals in the South), an estimated 38,000 deaths potentially could have been avoided.

While some of those deaths became the trigger for the public review of Sarasota Memorial’s practices, reading the 82-page report gives you a true sense of the magnitude of what went on in the SMH system during the pandemic.

In 2020 and 2021, it was the fog of war.

Sarasota County reported the first case of COVID-19 in Florida on March 17, 2020. Its staff had no inkling of what was about to occur.

Within a few weeks, SMH had 70 COVID patients. By July 2020, Sarasota County was averaging 200 new cases a day over a seven-day period.

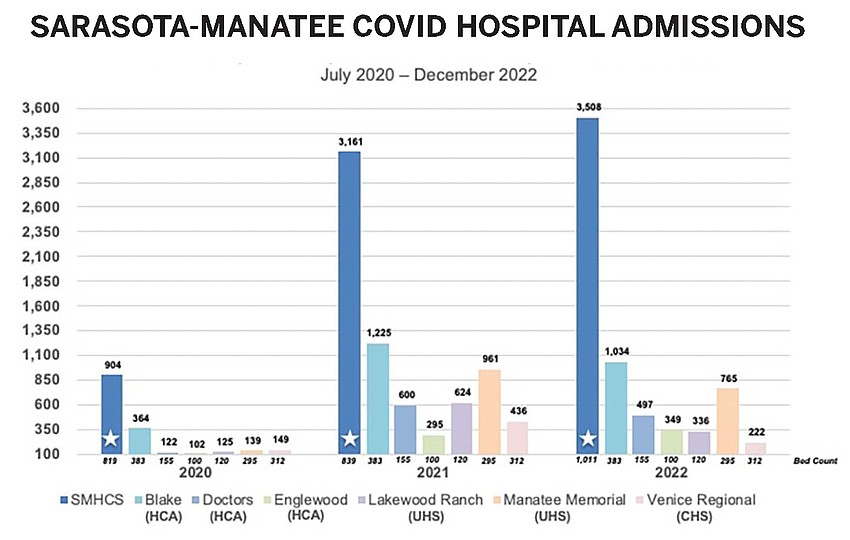

Altogether, SMH treated 13,731 cases and 70% of all hospitalized COVID patients in the county. Ninety-four percent survived; 768 died, as of this week.

The rapid rise in case numbers required SMH’s leadership and staff to react and improvise with the hospital’s facilities to avoid the worst that Americans feared.

Already at capacity when the outbreak began, the hospital’s leadership doubled its intensive care unit beds to 120; it shifted the use of several hundred beds and created 10 new care units to create isolation rooms. This is throwing out established daily routines for hundreds of staffers and implementing new, unfamiliar practices. Talk about disruption; this was worse.

A special supply-chain team scrambled to keep the hospital operating. The hospital’s biomedical engineers used a 3D printer to recreate a routine replacement part that manufacturers could not provide for respirator face shields. They figured out how to extend the life of N95 masks.

In 2021, the hospital used more than 273,000 N95 and isolation masks a month. Prior to the pandemic, typical usage was 2,400 masks a month.

Demand for COVID testing skyrocketed, causing the hospital to invest nearly $1 million in testing equipment:

Altogether, SMH processed 317,600 tests in the three years.

All of those demands required people to manage them, and leaders to coordinate SMH’s 9,000 employees — all of them on high-alert and wondering in 2020 and 2021 if they would be stricken with the deadly virus.

During the 2020 summer surge, more than 450 employees were unable to work because they contracted COVID. More than 400 missed work during the Delta wave in the summer of 2021. Infected employees jumped to 1,100 during the Omicron wave from December 2021 to February 2022.

In the midst of this, Sarasota Memorial hired more than 900 new employees in 2021 to prepare for the opening of the SMH-Venice hospital and the Brian D. Jellison Cancer Institute Oncology Tower. All of them had to be trained and onboarded.

The stress took its toll. Said the report:

“Sarasota Memorial offered around-the-clock counseling and support to help staff cope with the emotional strain, and provided ongoing wellness, stress reduction and resiliency training programs to help prevent burnout and fatigue.

To help keep the staff going, CEO David Verinder emailed more than 200 COVID updates from March 2020 through September 2022 — sometimes daily, often weekly, “based on the urgency.” The aim was to keep everyone informed “of the number of COVID patients in the hospital, positivity rates, deaths and other key indicators”; provide reminders and updates about COVID-related practices; and keep staff informed of what the hospital was doing to address the latest challenges.

While hospitals around the country saw record turnover, SMH’s turnover was lower than all of its peers. That played in the Gallup organization’s awarding SMH its “Exceptional Workplace Award” in 2022, citing the SMH staff for its “resiliency, determination and commitment to making their people a priority.”

Taken in context, that recognition is deserved.

But the underlying issue that spurred the election of four new board members and drew more than 500 people to two public hearings was this: how the doctors treated patients and families and the medications and protocols they prescribed during the pandemic.

That is the divide.

As a business in a crisis, you get the picture in the report of competent, thoughtful leadership and a staff committed to winning a war.

But at the same time, oddly, the public’s trust of what the physicians were doing deteriorated.

Patricia Maraia, one of three new board members who was part of slate of three board members elected in November, has been a registered nurse and patient advocate for 34 years. She was appointed vice chair of the study committee.

In her career, Maraia said nurses and doctors have always been willing to make suggestions and collaborate. “This time around was so shocking to me because so many voices were shut down. Open debate was not allowed.”

Maraia: “Bottom line was a lack of communication … I’m not saying it was intentional.”

Because of the speed at which the pandemic took off, “the medical staff was so involved in trying to figure this thing out that maybe communication got left by wayside,” she said.

She thinks fear “played a big role in the lack of people wanting to do things (out of the mainstream), because they were afraid it would increase the numbers or increase the deaths from COVID.”

Think back to 2020 and 2021, before vaccines. The national media became a mouthpiece for everything that came out of the CDC and Dr. Anthony Fauci. Day after day, he and his Washington colleagues drummed into people’s minds — including the minds of physicians — only certain treatments, drugs and protocols were acceptable. Everything else was quackery (Remember the ivemectin horse paste?).

And you could see it in hospital after hospital: The medical staffs lining up behind the so-called official scientists from Washington, D.C. SMH itself formed a task force of representatives from more than 20 specialties to vet and recommend treatments.

“Materials and guidance were updated regularly and covered all aspects of COVID-19 treatment … as well as review of evidence-based literature,” the study reports. “Each iteration included the latest recommendations from the CDC, NIH, WHO, Infectious Diseases Society of America and multiple medical societies.”

The task force also looked at the therapies and drugs that Fauci and other D.C. officials scorned — hydroxychloroquine and ivermectin. But as the sidebar shows, the picture that emerges can you lead you to this conclusion: Fear helped fuel group think — medical staffs throughout U.S. hospitals following the so-called science of the D.C. medical establishment.

Maraia: “As a practitioner, when you see that something is off label and really not recommended, that’s a red flag. You go: Hmm. I’m not comfortable, and right away you’re worried about litigation.”

Doctors at SMH and all over the country did not want to be associated with a small group of critical care physicians who challenged conventional wisdom — even if they had ample proof of the efficacy of ivermectin and valid arguments to be skeptical of the vaccines.

The scenario at the time was much like the entrepreneur who invents a world-changing technology, only to have the Establishment scoff at the invention and ridicule the entrepreneur as an outlier nut case.

But often times, it turns out that the nutty entrepreneur was right. He or she changes the world, while the establishment is left behind.

Given all of the unknowns at the time, you can’t fault the SMH medical staff for following its low-risk instincts. That’s one of its jobs — minimize risk.

But while the medical staff resisted alternative therapeutics and advocated for vaccines, the public over time became smarter and wiser. Trust for Fauci evaporated. And patients’ and families’ trust in their doctors became a widening fissure everywhere, including at SMH.

Maraia recalled a speaker at the first public hearing. He said: “Do you realize what you all have done? You have created such a distrust in the medical profession that I don’t know if it is ever going to be repaired.”

“That hit me very hard,” Maraia said. “To hear that was devastating for me personally and professionally.”

“That is what I am trying to fix,” she said. “Ultimately, that’s my goal — to bring that trust back to the medical community.”

The three-year review of SMH’s COVID practices was a start.

For one, the SMH board, CEO and medical staff deserve credit for conducting the review to begin with. The authors deserve credit for the detail in the report as well. It’s rare for hospitals to open themselves to such scrutiny.

But SMH’s leaders obviously recognized that as a tax-supported institution, they have an obligation to be open to inspection and respond to criticism and recommendations.

Appointing Maraia vice chair of the study committee also sent a message. “It was [the SMH staff’s] commitment to me that they were willing to work together,” she said.

That’s why, to some surprise, she voted to accept the report. The other two board members elected on the same slate as Maraia voted against accepting the report.

“I feel very good about the potential of where things are going to go,” she said.

Sarasota Memorial Hospital’s COVID-19 Study Review Committee published the following recommendations for the Sarasota County Public Hospital Board:

1. The formation of a Health Emergency Response Committee to help Sarasota Memorial effectively and efficiently respond to future operational challenges and public health events.

The COVID Task Force should serve as a model for an expanded rapid-deployment committee to provide a unified pathway for responding to unexpected clinical and operational challenges. We recommend that the Medical Staff work with administration to establish a Health Emergency Response Committee that:

2. Continued development of home health and post-hospital services and resources, including remote monitoring capacity to reduce the length of hospital stays and strengthen the community and health system’s resilience going forward.

As capacity issues continue to challenge the community and health system in the future, the ability to provide patients with step-down care after they leave the hospital is critical.

Particularly during surges, patients who are relatively less sick may be able to recover safely at home and in non-hospital settings with sufficient monitoring and support to face health challenges that develop after discharge.

We recommend that Sarasota Memorial continue to develop and expand resources to support discharged patients, including:

3. The deployment of more dedicated staff and increased utilization of technology, such as iPads, to improve communications with family members and between patients and their loved ones.

While the pandemic exacerbated the communication challenges in ensuring that patients, their families and caregivers face, the challenges are not unique to a health emergency.

We recommend enhancing the use of virtual meeting technology, including the use of easily available tablets and devices, to provide patients and their families with a convenient, reliable way to communicate when they cannot be physically together.

4. Build on established strengths in communications and information sharing by enhancing awareness of communication pathways for employees, medical staff and the public.

The pandemic posed challenges to the normal flow of information to and within Sarasota Memorial at a time when many people wanted to communicate with the organization. While Sarasota Memorial has a variety of established formal and informal communication pathways, not everyone was aware of all the communication channels available to them.

As Sarasota Memorial and the community it serves continue to grow, it is important to raise awareness of the different ways that patients, family members, physicians, staff and other community members can make their voices heard.

We recommend that Sarasota Memorial develop an outreach and education plan to highlight the ways that stakeholders can communicate anonymously or by name with medical staff leadership, senior administration, and the board.