- May 16, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

Fentanyl overdoses are devastating the entire country. In 2021, over 107,000 Americans died from a drug overdose, 71,238 of which were caused by fentanyl. In Florida alone, fentanyl ended over 5,000 lives the same year. This tragic crisis will not be resolved by doubling down on prohibition policies that have failed for decades and are actually fueling overdose deaths.

In a letter by Florida Attorney General Ashley Moody published in The Observer last month, she called upon President Biden to officially designate fentanyl as a weapon of mass destruction. The plea came a day after a House Energy & Commerce Committee hearing on the fentanyl crisis, which largely shared the same sentiment. Although much of the rhetoric blamed a porous Southern border, illegal immigration has little to do with fentanyl overdoses.

According to Customs and Border Protection, Southwest border encounters fell during the Obama Administration, increased during the Trump Administration, and have skyrocketed amid the Biden Administration — yet illicit opioid overdoses (like fentanyl) rose every single year of each presidency. Indeed, fentanyl increasingly infiltrated the country while President Trump reduced the unauthorized immigrant population. The fact of the matter is that the vast majority of fentanyl is trafficked through ports of entry and carrier packages — not on the backs of illegal immigrants and trafficker coyotes. And unfortunately, there’s no amount of enforcement that can stop it. In fact, it’s the enforcement itself that has led to fentanyl being the preferred drug of traffickers, and labeling fentanyl as a WMD would only lead to more concentrated illicit drugs.

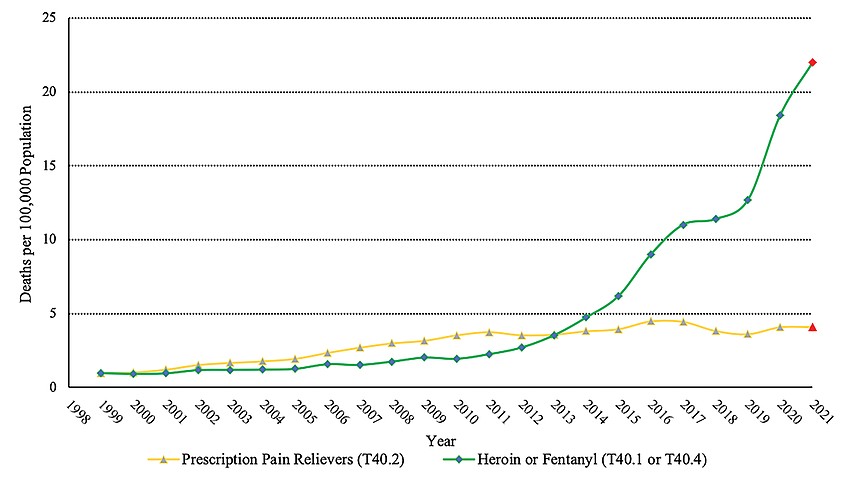

Heroin overdoses began to increase in 2011, the year after law enforcement began mandating reductions in opioid prescribing across the country. Indeed, opioid prescribing rates have decreased every single year since 2010, and it is no coincidence that overdoses from black market opioids have increased in tandem, as CDC data in the accompanying figure shows. Attorney General Moody’s aggressive policies on prescription opioids doubles down on the very cause of the overdose crisis.

Drug Enforcement Administration data show that as heroin seizures rose over the past decade, production of heroin in Mexico began to decline. Simultaneously, drug enforcement increasingly encountered fentanyl. Although illicit heroin has a high overdose potential, it is still much less potent compared to fentanyl. But it was the success in heroin seizures that motivated drug traffickers to begin engineering more potent substances, so that they could more easily conceal the product while transporting. During alcohol prohibition in the 1920s, bootleggers stopped supplying beer and wine in favor of liquor, since it was easier to conceal from police and provided more “bang for the buck” so to speak. These same incentives have motivated the cartels to supply fentanyl instead of heroin.

Now, after the Drug Enforcement Administration’s record year of fentanyl seizures in 2021, a new drug that can be 20 to 100 times stronger than fentanyl — isotonitazene — has started to appear more and more in the toxicologies of drug overdose victims. There is a pattern of futility here in addressing the problem with more prohibition. If Congress labels fentanyl as a WMD, the U.S. will increasingly see drugs like isotonitazene in the country and even more overdoses.

Some may think that there has been an increase in opioid addiction in the U.S., but the Substandard Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration reports that opioid use and addiction have both been dropping since 2015, and in fact the misuse of opioids in the U.S. is now at its lowest rate in over 20 years. The only reason why so many more people are dying is because the illicit drug market is so dangerous — not because there are more drug users.

If we were to offer both legitimate pain patients and those addicted to opioids safer legal alternatives to cartel-supplied drugs, we would see a massive decrease in death. Punishment rarely convinces those with drug abuse problems to quit, but help addressing their problems that cause drug abuse does. But that requires weaning them off the drugs, which is hard to do with prohibition. Prohibition also creates massive incentives for violence and ever more unsafe versions of drugs, creating an environment where helping drug users is very difficult. It’s a circular problem and we have to break the cycle.

But until our policymakers recognize the factual reality that prohibition keeps failing, and doubling down on it with a WMD declaration is only doubling down on failure, expect drug overdoses to continue to rise.

Adrian Moore is vice president at Reason Foundation and lives in Sarasota. Jacob James Rich is a policy analyst at Reason Foundation and a researcher at the Cleveland Clinic Center for Value-Based Care Research.