- June 1, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

Even though there are no coral reefs in Sarasota area waters, local residents and wildlife will still reap some benefits of coral reef restoration efforts spearheaded by Mote Marine Laboratory & Aquarium following a nearly $7 million grant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

“What it means for Mote is not all that important when compared to what it means for the coral reefs of Florida and the world,” said Michael Crosby, Mote’s president and CEO. “It’s a grant that now allows Mote and our scientists to really build upon an incredible history of research that we’ve been working on in the Keys now for 30 years.”

Since starting restoration efforts, Mote scientists have had success in restoring over 200,000 corals.

The Transformational Habitat Restoration and Coastal Resilience Award allows Mote to take a leadership role in partnership with NOAA in a “holistic, community-based restoration effort.”

The grant will cover a four-year, multi-faceted project focused on implementing a holistically transformative coral reef restoration initiative at 10 reef sites along Florida’s Coral Reef, just offshore of the Florida Keys Archipelago, according to a news release from Mote.

Seven of the 10 reefs being targeted are NOAA’s iconic reefs and include:

All seven iconic reefs are within sanctuary preservation areas or areas where activities such as fishing and anchoring are prohibited or tightly regulated.

“That only accounts for a fraction of a percentage of the reefs in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary and Florida’s Coral Reef,” Coral Reef Restoration Research Program Manager Jason Spadaro said. “We wanted to include a series of sites that were outside of those protections to really demonstrate that we can do restoration in these areas where the public is allowed to use the resource.”

The remaining three reefs are in waters where people are more likely to recreate.

“We want to make sure that restoration is going to work in areas where the public is allowed to use the resources in those extractive ways,” he said. “If we need to go back to the drawing board and redesign how we are doing restoration in zoned versus non-zoned areas of the reef.”

Living coral cover, the proportion of the reef covered in living coral, on Florida’s Coral Reef is currently between 1% and 5%. The number is dramatically less than about 40 years ago when coverage was more than 30%.

“Mote is all about restoring the entire coral reef,” Crosby said. “(The grant) also allows us to really have a statistical analysis approach of adaptive management strategies both within those seven iconic reefs and outside of them.”

Not only can extra work be done, but the additional funding allows Mote scientists to take additional time to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of programs that have already been in place.

The initiative, which is led by Spadaro, is seeking to expand the laboratory’s capacity to continue making strides toward restoring coral reef habitats. It is more than just outplanting coral. The work also focuses on placement of key members to a coral reef ecosystem such as Caribbean King crabs, which help keep down growth of macroalgae on the reefs. Twenty-five percent of the biodiversity of ocean species across the globe exist on coral reefs, Crosby said.

There is more than one way to restore a coral reef, but the primary method, and the one Mote is pursuing, is called direct or active restoration.

“You’re literally cultivating pieces of coral and then putting them back on the reef or outplanting them onto the reef,” Spadaro said. “The goal isn’t to literally restore the reef. We’re not trying to produce or outplant the same amount of coral that we want to end up with. We’re trying to do it in a thoughtful way, so that we place corals in different genotypes within close proximity so that their probability of reproduction is much higher.”

In Sarasota, Crosby said, between 50% and 80% of oxygen we breathe comes from plants in the ocean.

“To be able to produce that oxygen, requires a very healthy rainforest of the sea — coral reefs,” he said. “If you want to continue to breathe and live, you need a healthy coral reef.”

A Caribbean king crab hatchery is being completed at Mote’s Sarasota campus and is set to be operational in the near future. This species of crab will be placed in the 10 targeted reefs and are crucial to restoration efforts as they graze on macroalgae that would otherwise compete with the corals that are being put out.

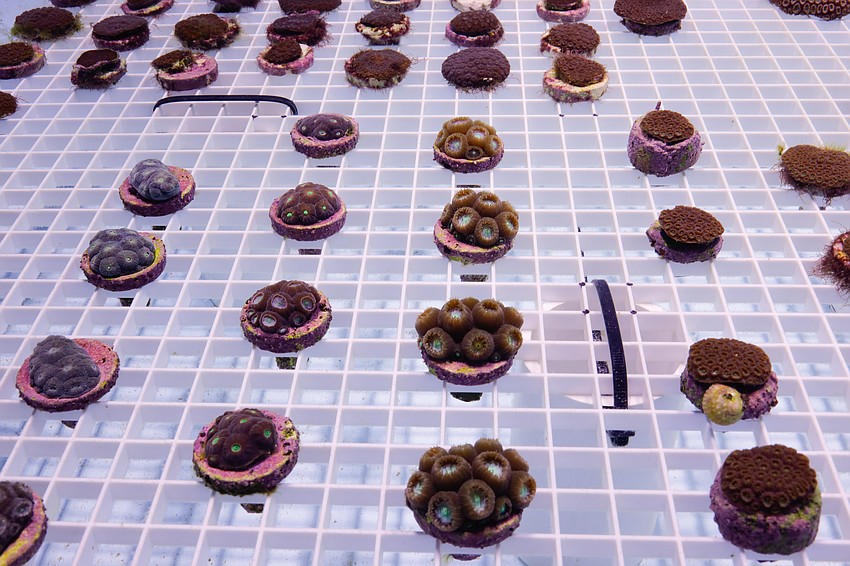

The Sarasota campus is also the home to the international coral reef bank that has 6,500 genotypes of coral species being used to outplant in the Florida Keys and elsewhere across the globe.

“Sarasota is sort of that focal point for much of the research that is being implemented in the coral research and restoration program,” Crosby said.

No. Sarasota borders a region where there is a shift from corals as a foundation species to sponges and oysters. The Sarasota area does not have the right conditions for a coral reef ecosystem to thrive.

“There are reefs,” Spadaro said. “They’re just not coral reefs.”

The absence of coral reefs is largely due to latitude. By coral standards, the Sarasota area gets too cold.

“There are some reefs that occur further north, but they tend to be well offshore and deeper where the loop current keeps them warm year-round,” Spadaro said.

The Gulf of Mexico is not particularly conducive to coral reef building because it is categorized as a more temperate ecosystem. Moving north into temperate latitudes, the water gets cold enough in the winter that nutrient loads increase and can lead to microalgae blooms.