- July 11, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

It’s not the job that pays the bills, but it’s the one that he’s most passionate about.

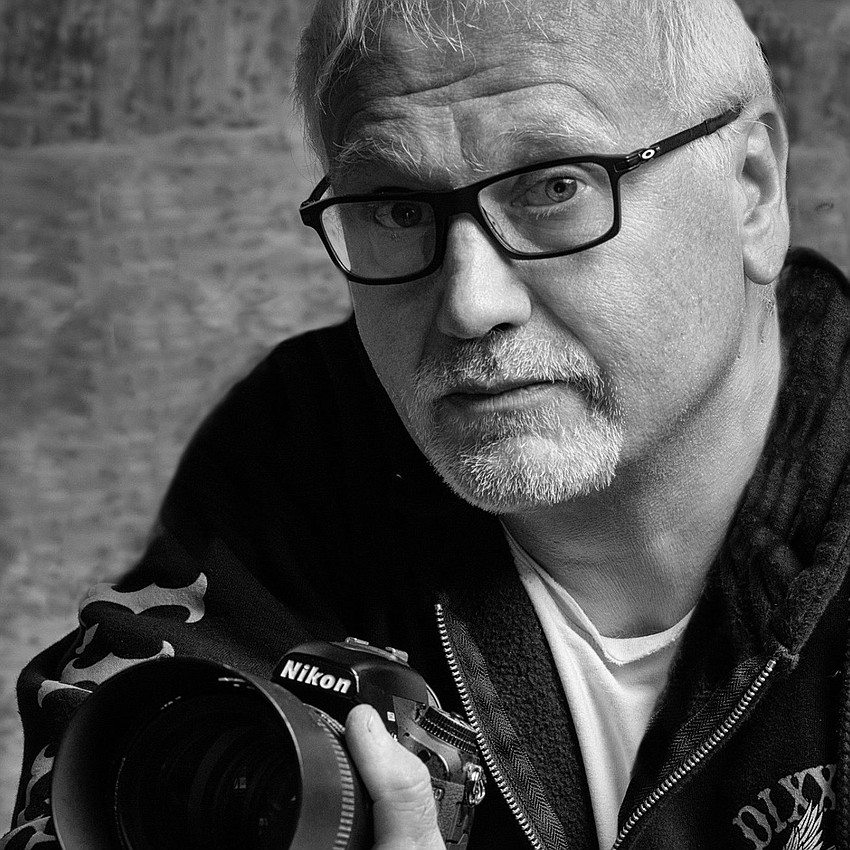

Allan Mestel has photographed the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent exodus into Poland. He’s captured scenes of homelessness in Sarasota and Bradenton. He also owns the Longboat Key gym Beach Fitness 24/7 with his wife and runs a photography studio in Bradenton.

Most recently, Mestel was in Brownsville, Texas, shooting photos at the U.S.-Mexico border for five days in the lead-up to and aftermath of the May 11 expiration of Title 42.

The public health restriction was implemented in response to COVID-19 and allowed U.S. officials to quickly turn away migrants and deny asylum seekers “on the grounds of preventing the spread of COVID-19,” according to the Associated Press. “(there) were no real consequences when someone illegally crossed the border.”

After Title 42 expired on May 11, the U.S. returned to the stricter policies of Title 8 under which, “Migrants caught crossing illegally will not be allowed to return for five years and can face criminal prosecution if they do,” according to AP reporting.

The Observer spoke with Mestel shortly after he returned from his trip where he took thousands of photos of migrants, their living conditions and the border itself.

Basically, I spent the bulk of my career as a TV ad director and photographer in Canada. It wasn't until I moved to the U.S and set up my own studio that I became more interested in documentary-style photography. I got more interested in 2016 with the election and … social justice movements.

I became involved with an activist group, Witness at the Border. I ended up at the border in 2019 photographing both sides of the border. I’ve been all over the border in Texas.

I went to Brownsville, Texas. I have contacts down there, with Team Brownsville. They are a team of volunteers who provide resources as best they can to (migrants). … I made contact with them once I was in Brownsville and I did some shooting there. The international bridge in Matamoros is just a short walk across the Rio Grande.

The lens provides its own commentary. My feeling was that for most people, they don't have a chance to go to the border. To some degree, they are held hostage to the narrative that's in the media. My intent was to provide, for those who choose to seek it out, a pretty comprehensive visual narrative of what is happening at the border. My pictures are what they are.

I have certain protocols I adhere to when shooting people who are living in adverse circumstances. I never shoot down. If people are sitting or lying down, I crouch down or lie down. I want people to look at the subject eye to eye. I never want to be looking down on people

I try to isolate a subject so you're always looking at an individual. When I shoot with a wide lens I tend to shoot very close to the subject, so you're getting a sense of immediacy. I like for the audience to look at an image and feel that they are there with someone they can't look away from.

I'm really conscious of not engineering a photo so it feels staged. I will shoot with minimal interaction — just enough to feel that I've got the consent to shoot. It’s very much a process of feel.

A thousand a day. And then that culls down to whatever I feel are the best images and most representative images.

On Friday, the day after Title 42 was lifted, the bridge was pretty hectic. There’s a lot of traffic back and forth. A lot of people live on one side and work on the other.

I’ve been in migrant camps and refugee camps quite a bit. I was in Ukraine a week after the war started.

I'm always amazed by how upbeat the camps at the U.S. border are (despite) the people there living in the most primitive conditions in the Western Hemisphere. People are living in structures constructed with sticks and tarps. The living conditions are hellish.

Most of the migrants were from Venezuela. To think of the journey they’ve had through the Darien Gap, the jungle and some of the most violent countries in the world, mostly on foot — to make that journey and end up in that camp at the border and still have hope. There was definitely despair, but for the most part there was a sense of hope whether it was realistic or not. The chances of actually getting asylum under the current rules are very difficult.

On Thursday, the border was reinforced. I couldn’t believe how much heavy equipment came down to the border. The Texas Guard had strung two layers of razor wire and stationed National Guardsmen all along the river. There was a significant increase in the militarization of the border. I didn't see anyone swimming the river. I saw far less activity.

Most people were adhering to the protocol, which was to download the U.S. Customs and Border Patrol application. For the most part, these people would rather do it the right way than the wrong way. Under Title 42 there really wasn't much of a process. People would be immediately deported without the chance to have a credible hearing, which is the start of the process to seek asylum. At that point they are then given a court date to defend their claims (to asylum). Most would rather go through the process.

Illegal crossings plummeted. The stat I think I saw was by about 50%.

There has been a demonization of migrants. I think there's a perception that the majority of migrants are looking to cross the border as criminals. I think if people could go to the border and see who is actually living there they would be surprised. It’s families, looking for an opportunity. They're not looking to come to the U.S. and involve themselves in criminal enterprises.

I have heard rhetoric that the camps are filled with military-age members, gang members — what you see at the camp, and it's evident in the photographs is that it's mostly families. Everyone from teenagers to babies.

The majority of people that I interacted with want to (enter the country legally). They want to come and do their best to convince a court that they are legitimately afraid for their lives or are living in conditions in their home country where they are in fear due to the levels of crime. Most of these migrants are Venezuelans escaping human rights abuse and persecution. Why do we not feel they are entitled to take advantage of the asylum law?

The amount of time and energy I devote to this makes my wife a little homicidal (laughs), but this is my passion. The only reason she doesn't put the kibosh on it is because I'm like a feral cat. I really do love it. There’s nothing that makes me happier than going into the field. It’s just fascinating to me how resilient people can be living in circumstances that I can't ever see myself in — and how people can find ways to be happy. I just don't know how they do it. I guess necessity and pure resilience.

It's not enough to make a living, but I do what I can to make it pay for itself. Ultimately there is some cross-pollination. There is some hope that exposure from this work will translate into more work.

It’s a faint hope, but the only way the border situation gets resolved in some way that is sane and that is a win-win for the country and those who are looking to make a life in this country is for there to be a comprehensive review of immigration law that looks at labor needs realistically and that looks at the labor resources south of the border; there is a labor shortage at the lower end of the ladder, and immigrants would provide an enormous resource for that to be filled. Find an immigration solution that is consistent with supply (migrant workers) and demand (jobs). The larger picture is that this country needs immigration. We are not producing people who will be able to fill the needs of certain industries.