- July 17, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

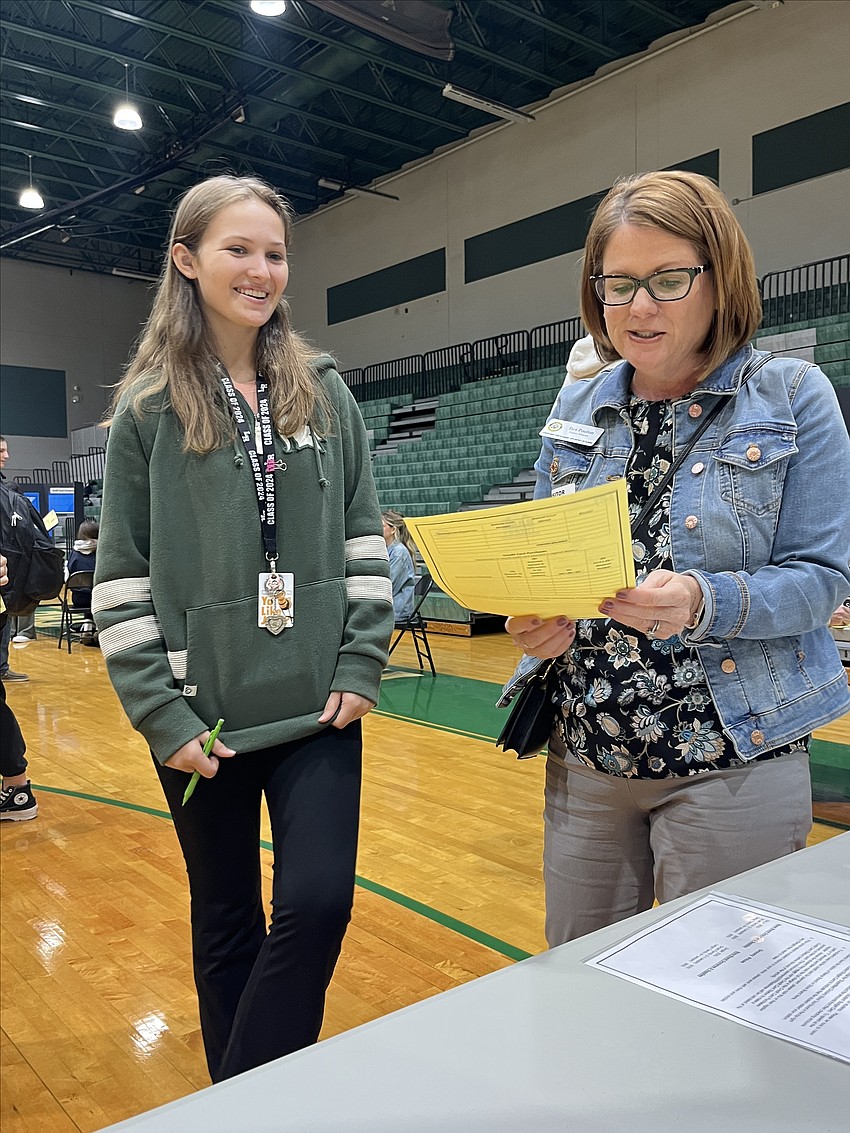

Rather than being a senior at Lakewood Ranch High School, Cayman Corscadden stepped into the future on Nov. 6-7.

In this case, Corscadden was living life as a personnel recruiter, and setting up her finances on the salary that goes along with it.

It was part of the Manatee Chamber of Commerce’s Big Bank Theory.

Students had to figure out how they would afford housing, insurance, childcare, transportation and the other necessities and luxuries of life. In Corscadden's case, it had to be accomplished with a monthly income of $4,333.

She had a spouse who earned $1,000 monthly along with a 3-year-old daughter to support. After taxes, she had $4,206.42 to spend monthly.

The Manatee Chamber of Commerce had 14 stations for seniors to work on their particular budget.

Although Jacki Dezelski, the president and CEO of the Manatee Chamber of Commerce, suggests students prioritize housing, transportation and childcare before spending money on other expenses, not all students had the same priorities in mind.

Corscadden’s first stop was at the “That’s life” station where, like in real life, the students experience financial ups and downs. She had to randomly select a card that would either give her financial troubles or add to her income.

Cards ranged from “your brother is moving in and he’s paying rent; add $100 per month to your account” to “happy birthday! You received $50 from your dad” to “your toilet is leaking; pay a plumber $75 for repairs” to “you need to get a prescription filled and your insurance doesn’t cover the full cost, pay $125.”

Corscadden received an unexpected bonus when she received $50 from a scratch-off lottery ticket.

In selecting priorities, Corscadden went to purchase groceries first. She had to decide whether the cost of name brand groceries was worth it or if she should opt for the generic brands.

“The discount groceries are going to be just as good as the name brand,” she said.

To feed her family, $500 was deducted from her monthly income.

Corscadden’s next stop was to set up utilities. She had not yet determined her housing situation, so a volunteer walked her through her utilities options based on her potential housing.

With a two bedroom, one bathroom apartment, she had to spend $150 for gas, electric and water. Then came more decisions.

Did she want a cell phone? Yes. That’s $80.

Did she want a cell phone for her spouse? Yes. Another $40.

What about internet and cable? The bundle cost her $60.

“It was weird that buying internet and cable was less than buying one,” she said. “It was a good deal.”

Corscadden’s balance was down to $3,426.42. She was getting nervous. She hadn't even paid rent yet.

In the real world, she has thought about becoming a zoologist, but during the exercise, she began to learn lessons about the cost of living.

“(Zoologists) don’t make the most amount of money,” she said. “I might have to rethink my life, but I think you have to love what you do. If you love your job and make enough to live, what you have is enough.”

Back to the exercise, Corscadden settled on a two bedroom, one bathroom apartment. With renters insurance costing $25 and rent being $1,900. Now reality was hitting hard.

She gasped at the balance of her bank account, which was down to $1,501.42.

“I’m getting a second job right now,” Corscadden said.

With a draw of a card, Corscadden she picked up a second job at a grocery store. She decided to work there four nights per week, adding $640 to her monthly income.

“I still feel poor,” she said. “I’m not going to make it through everything. This is a lot harder than I thought it would be.”

Corscadden’s life wasn’t about to get any easier. It was time to pay for insurance.

With her spouse working, she decided he would cover his own health insurance, but she would be responsible for covering the cost of health insurance for herself and her daughter. That was $350 a month.

Dental insurance was another $40 for her family.

Out of the three options for life insurance providing coverage between $60,000 and $200,000, Corscadden decided to go down the middle and spend $22 per month for $120,000 in coverage.

“The middle was double the lowest, so that’s enough,” Corscadden said of her choice.

As Corscadden made her way to the transportation station, she saw her insurance costs were not done. She needed auto insurance.

But before she decided on transportation, Corscadden discovered she could go back to school to earn a masters degree with the hope of being able to earn more money for her family.

The choice to earn a higher degree didn’t pay off as she had expected. Although she received a $100 a month bonus for going back to school, it cost her $350 a month to earn the degree. She received $50 a month in financial aid.

She had $1,529 left in her budget.

Corscadden realized she needed to provide childcare if she and her spouse were working. Another reality check set in as she saw the cost of childcare. She could either pay a babysitter $15 per hour, pay $300 per month for a relative to care for her daughter, have her spouse stay at home and give up his $100 a month salary, or pay $800 per month on child care.

Corscadden opted to pay a relative $300 a month for childcare.

“Childcare is a lot more than I thought,” she said.

After putting it off as long as she could, Corscadden decided it was finally time to get a car.

The decision making continued. Should she buy a new car or a used car? Whichever she chose, what type of car should she buy?

With new cars costing between $354 and $716 per month, Corscadden decided a used car would be best, and she went for the cheapest option: a Kia Sportage for $323 a month. Then she needed to add auto insurance for $200 a month.

Her bank account had $706 left in it, and the 50-minute class period was over. Corscadden was overwhelmed, knowing she had another day of decision making ahead of her.

When Corscadden returned to the Big Bank Theory the following day, her first stop was to open a savings account where she would put away $50 a month.

Then she decided to get a credit card and used it to purchase clothing for $200 for her family as well as a music streaming service as entertainment for $20 per month.

She finished the game of life with about $500 for the month.

“It was a lot more than I thought I would have left,” Corscadden said.

The game forced her to analyze her priorities and question every expenditure.

She wished she has changed things around so she could have spent more money on childcare and she also would have spent more money on her car.

"If it’s new, it’s in better condition," she said of the car. If you have a used car, it’s more likely to break down. That’s going to cost you more in the long run.”

Corscadden’s biggest takeaway?

Prioritize, plan ahead and save as much as you can.

“My savings plans haven’t been as good as they should be, and now I really need to save after seeing how much things actually cost in the real world,” she said.