- May 10, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

Walking onto the Gulfside Road beach access, a recently unearthed seawall stands out among a row of large rocks.

Before Hurricane Idalia, people may not have even realized there was a seawall buried there.

This was one of the most striking differences in the beach that Longboat Key resident Cyndi Seamon saw after the storm.

Seamon is also vice president of the Longboat Key Turtle Watch. She was on the beach before and after the storm conducting turtle patrols.

Near where she lives on the north end, Seamon said she noticed a lot of the beach was lower and sand moved to the dunes.

“We just noticed how much water the dune system held,” Seamon said. “It’s amazing how well they do.”

Further south, she noticed more of an escarpment, where sand steeply drops between the dune and beach face.

What impressed Seamon, though, was how well the beaches — and the vegetation — did the job of holding up against storm surge.

Before Hurricane Idalia brushed past Longboat Key, Public Works Program Manager Charlie Mopps believed that storm surge would be the main concern for the island.

Mopps has been working on beach building since the 1990s. He studied marine affairs at University of Rhode Island.

He was optimistic that the beaches would hold up to Idalia’s surge.

Afterward, he went to look at the beaches and saw what he called “deflation,” i.e. a flatter beach profile. But that’s not necessarily a bad thing.

“Our beaches did what they were supposed to do,” Mopps said.

Beaches are built and replenished for three main reasons, according to Mopps.

One is for the environment, creating breeding grounds for turtles and birds.

Second is for recreation.

And third are the storm protection benefits.

“That’s why we do what we do as a town to replenish our beaches,” Mopps said.

The last time Longboat Key completed a beach nourishment project was in 2021. In that $36 million project, 1 million cubic yards of sand were excavated from the Gulf and the inlet to go to the beaches.

In 2016, a smaller project brought sand by truck and from the inlet. That $20.28 million project implemented 43,000 cubic yards of sand.

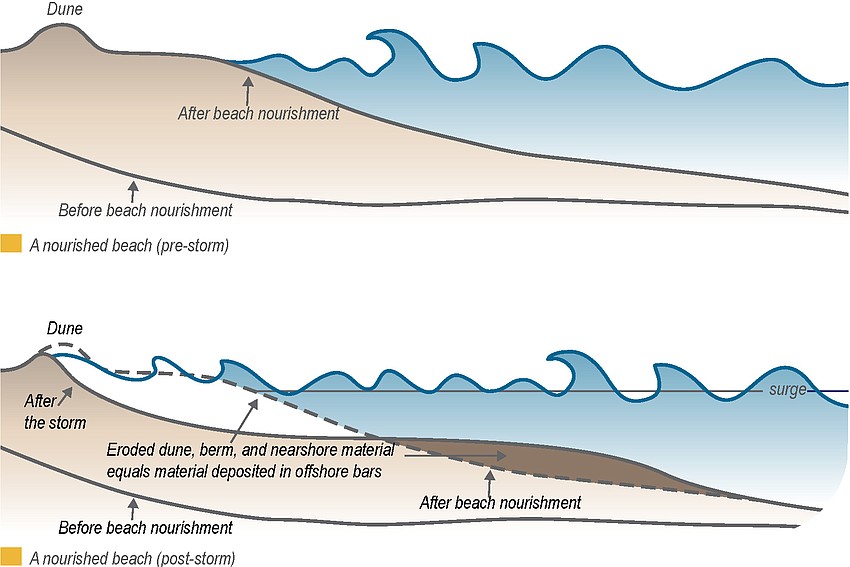

A beach’s berm is one of the top things Mopps said will mitigate the impacts of storm surge.

The berm is the area between the high-tide line and the dune, and it acts as a physical barrier against waves. As waves crash, sand will be pulled offshore from the berm area, which then moves back the breaking point of the waves.

Because of this, Mopps said the beaches may appear to lose some recreational area once the storm has passed, but the sand will naturally accrete back over time.

Longboat’s beaches are built to a 5- to 6-foot berm height, Mopps said.

“Where we had the higher berm elevations, there was very little to no overwash,” Mopps said. “But because of that, the beaches did suffer an impact, which is that they kind of lost some of their elevation.”

Behind the berm is the dune, which is like a “final frontier,” as Mopps described it. If water gets past the berm, the dune is the last protector for the upland structures.

Vegetation within the dunes helps to secure sediment in place, providing an extra layer of protection against the surge.

All parts of the beach serve a purpose, Mopps said. Each is designed to absorb impacts of a storm.

Seeing the deflated beach prompted Mopps to reach out to coastal engineers to begin surveys.

The surveys will take about a month to complete, Mopps said. But the results could allow him to pursue a FEMA claim, which could provide funding for a future nourishment project.

With hurricane season still active, Mopps couldn’t speculate on how a changed beach landscape would affect future impacts.

“There’s still plenty of beach, there’s still plenty of berm,” Mopps said.

Beaches usually take the brunt of storms, Sarasota Bay Estuary Program Executive Director Dave Tomasko said. And it’s important to continue placing importance on beach nourishment.

But with the latest flooding on Longboat Key from Hurricane Idalia, he said the greater issue is on the bay side.

Beach nourishment won’t solve all the flooding problems, Tomasko said.

While the dunes and berm protect the gulf side, that doesn’t help the bay side from getting flooded — especially in low-lying areas like north Longboat.

Through anecdotal evidence from north Longboat Key residents, Tomasko heard streets are flooding more often.

It’s like a perfect storm of cause and effect.

Tomasko said spring tides occur with new and full moons, and king tides are a special, more severe kind of spring tide.

But now, it doesn’t take a king tide to flood low-lying streets.

Over the last 20 years, Tomasko said there has been an estimated 6 inches of sea level rise, and another 9 inches is expected over the next 30 years.

“So what's happening now is, the water level is higher, causing more street flooding, more often,” Tomasko said. “And that’s not going to get better, that’s going to get worse.”

Because most of the bay side is private property to the water line, and much of that coast is made of hardened shorelines, there aren’t many options to address the issue.

Tomasko said there are some critics of beach nourishment, and others that think people should retreat from barrier islands all together.

“That’s not a conversation that’s going to get a lot of traction,” Tomasko said.

Beach economics, especially with barrier islands, are too important to ignore. Healthy beaches are necessary to those economies, according to Tomasko.

He said some other places try to harden beaches, or implement piles of rocks to protect the shoreline.

“Beach nourishment is probably the least long-term damaging way to keep those barrier islands in place,” Tomasko said. “But it’s going to happen more often in the future with sea level coming up and storms becoming more violent.”