- May 29, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

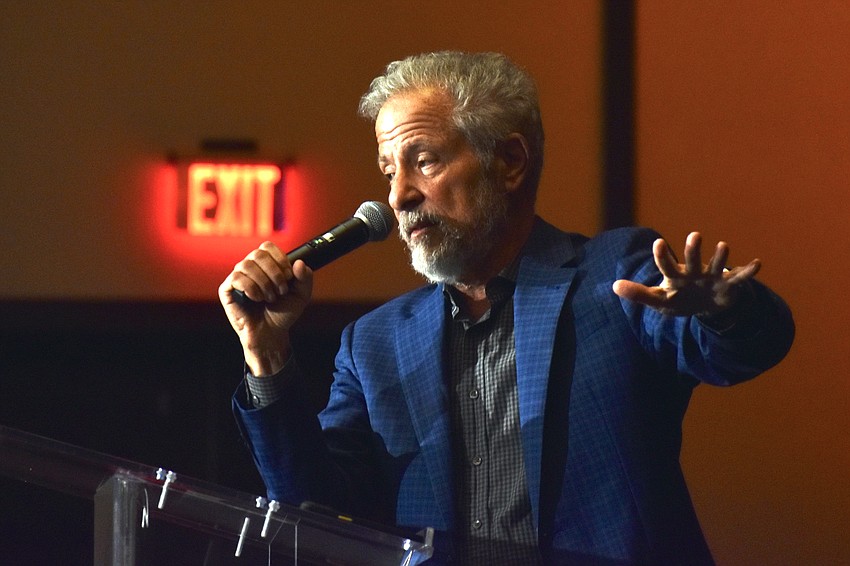

Just like anyone else, Andrés Duany has strong opinions on the state of Sarasota.

The difference is he's the founder of DPZ CoDesign, the principal consultant for the current Downtown Sarasota master plan.

So when he renders his appraisal of the city, people take notice, like on Jan. 24 at the Art Ovation Hotel when he addressed a crowd of hundreds to kick off Architecture Sarasota's lecture series “Downtown Sarasota: Hindsight, Insight and Foresight.”

The currently sold-out series, which also features David Houle, Mitchell Silver and Victor Dover, is designed to spark public conversations about how best to manage the future of the downtown area.

Duany, the architect, urban planner and “father of New Urbanism,” spoke with a bluntness that provoked laughter as he voiced views that might ruffle the feathers of those apprehensive about the city’s growth and of large developers.

Don’t try complaining to him about loud music, for instance.

“It was kind of interesting that this place was such a princess with a (capital) ‘P’… that (loud music) was considered trouble,” he said, while suggesting the sound not be amplified.

It's been about 15 years since his last visit, and overall Duany is pleased with what he sees.

In 2000, he came to Sarasota and, with his team of planners, created a blueprint which grew to encompass more than 40 separate projects and became the current downtown master plan, Downtown Sarasota 2020.

He said today that what he finds in Sarasota is contrary to what he has heard about, a town “full of promise.”

Duany repeatedly praised features of the town like the breezeway, lighting, landscaping and multiple blocks of retail and social space, something he said is a rarity in the nation.

Yet Duany didn't mince words when it came to something he takes issue with — for instance, what he says are excessive parking lots, something that runs counter to the walkable, environmentally friendly towns favored by the design philosophy of New Urbanism.

Sarasota’s bayfront, which features the problematic lots, doesn’t even have a proper name, he lamented to the Observer.

“Have you seen the one in Nice? Have you seen the one in Havana? Have you seen the one in Rio? Have you seen yours? It is such a collection of incoherent junk,” he told the audience.

He thinks his criticism does the opposite of undermining his praise. As he told the crowd, “If you know me, you know that if you were doing a lousy job, I would tell you, so when I say you’re doing a good job, trust me.”

He emphatically drew a distinction between New Urbanism, which he favors, and suburban sprawl, which he sees as opposing what he believes in — a livable, aesthetically appealing social space.

According to Duany, suburbia betrayed its promise to make life better, instead creating a landscape defined by parking lots and beneficial to neither people nor the environment.

“Have you heard that Lakewood Ranch is the fastest-growing community in the United States?” he said. “That’s a horrible idea.”

He also lamented what he said is the loss of a time when people were excited for progress, when developers were seen as the heroes moving the world into the future, instead of as the enemies.

Duany said the voices of the entire community should be heard — not only those directly impacted by a project. But he said this is not what is occurring. Although development is for the younger generation, he said, it is the older population who tend to show up to hearings.

He floated the idea of a citizen’s jury process for developmental decisions, something currently utilized in Australia. Indeed, placing the decisions in the hands of society is often a priority for Duany.

“No one can actually develop a lot here,” he said. “They have to be a big-deal company that can sustain not only the purchase of the four or five lots, but can hire the consultants, pay the extra underground pipes, and by the way, pay for two years of owning that land while you get a permit.”

He believes subsidies for new developments, like affordable housing incentives, make issues worse. Developers whose unit numbers are limited will only build bigger and wider, he said, creating a “coarse” downtown. Instead, he said, transfers of development rights are the key to filling the need for new developments.

Meanwhile, he thinks regulations of the Southwest Florida Water Management District requiring developers to retain water on-site are among the rules shutting out smaller developers. These laws, he claims, were meant for greenfield land, not for urban areas that already have water management systems.

Ultimately, Duany described a good living space as being about “where the building meets the sidewalk,” and he thinks architects are up to the task of creating it.

“The architect will converse; they want to get your permit,” he said. “And so, you're really more powerful than you think. By the way, you can't really deny them a permit, but you can take longer.”

He favors measures like requiring the largest and best trees right from the start of a development, avoiding gaps in the urban fabric and including parking spaces between sidewalks and the road to create a buffer between pedestrians and traffic.

Speaking in the same vein, he even managed to wedge himself into the roundabout debate.

“What stops traffic is the red light,” Duany said, calling roundabouts an obstacle for pedestrians. “If I were to come up with a very simple rule, I say every intersection should have a traffic light, and the cycle should be no more than one minute.”

Don’t try asking him about the presence of the city’s homeless population.

“I met a few, and they're not trouble, they’re just not. So, do you have another problem you want to invent?” he said as he concluded his response during the Q&A session.

Whatever the issues may be, his belief is that the answer is progress — not looking backwards.

Duany told the Observer that his three main priorities for the downtown area are cleaning up the waterfront, enabling smaller developers by reducing regulations that block smaller projects by younger people and expanding the success of Downtown Sarasota out to U.S. 301.

“This is the success of the prior generation, right? Twenty-five years ago,” he elaborated. “And the new people, the younger people, tend to try to inhabit the success of others. They need to be pioneers.”