- April 4, 2025

-

-

Loading

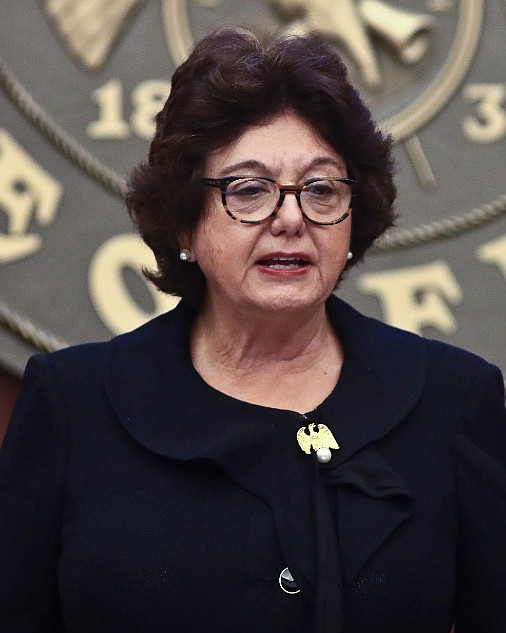

You have to give Florida Senate President Kathleen Passidomo, R-Naples, credit. When her colleagues tapped her three years ago to become Senate president during the 2023 and 2024 legislative sessions, clearly, she decided to go big.

Rather than become a warrior in Ron DeSantis’ angry culture wars, Passidomo instead decided to take on two of Florida’s most nagging, difficult and important issues — the shortage of affordable workforce housing last year; and an increasing shortage of health care practitioners (doctors, nurses, dentists, mental health specialists, etc.) in the current session.

The legislation she has shepherded and persuaded both houses to adopt — the Live Local Act in 2023 and this year’s Live Healthy Act, Senate Bill 7016 — at least on paper and in theory, has the ingredients to boost supply and allay shortages.

Of course, with legislation, we know it’s always about the incentives — picking winners and losers and who pays and who receives. In five years, we’ll know: Passidomo will be either a goat or one of the Senate GOATs.

For now, she is the nonboisterous, unassuming lawmaker who believes wholeheartedly her job is to serve Floridians, not pursue the next office up. She cried on the Senate dais when her colleagues named an amendment to her health care bill after her late father, an ophthalmologist. “He always taught us to give back,” she said.

As Senate president for the 2023 and 2024 sessions, Passidomo has had enormous power to give back. In her role in Senate leadership, she has seen how the workforce housing and health care practitioner shortages are two major issues affecting every Floridian. What’s more, since the pandemic, they have become increasingly menacing and acute conditions that, if not addressed, are sure to drag down Floridians’ quality of life and strain the state’s economy in coming years.

They already are.

You know it. Just about every employer has experienced hiring someone who wants to move to Florida, only to have the new employee turn down the job because housing was too costly. The cost of housing is pushing up the cost of labor and everything else.

And surely everyone has experienced trying to make a doctor’s appointment, only to be told the earliest you can be seen is three months from now. That wait time is going to get worse.

State demographers expect Florida’s population to continue to grow more than 300,000 people a year for the next five years. What’s more, by 2030, Florida’s 65-and-over population — the biggest consumers of medical care — is expected to rise from 21.3% to nearly 25% of the state’s population. That’s almost two million more seniors.

In a January assessment of Florida’s physician shortage, Florida TaxWatch reported:

“In 2030, Florida’s supply of family medicine physicians, general internal medicine physicians and pediatric physicians is expected to meet only 62%, 65% and 76% of demand, respectively.” Similar shortages exist in the specialties.

You think seeing a doctor is bad now; TaxWatch says: “Florida will need to fill 22,000 vacant positions by 2030. Nationwide, this supply demand gap is second only to California.”

To counter this and at the same time take steps to make medical care more accessible to low-income Floridians, in the spring and summer of 2023, Passidomo marshaled her Senate health care staff and recruited Sen. Colleen Burton, R-Lakeland, to craft a far-reaching bill. By the time SB 7016 made it to the Senate floor, it was 232 pages.

Sen. Gayle Harrell, R-Stuart, remarked on the Senate floor: “This is the most amazing piece of legislation I have seen in 22 years. It also happens to be the largest piece of legislation that I have read in many, many years.”

There are so many parts to the bill, when Burton introduced it in a Senate Fiscal Policy Committee hearing, it took her 22 minutes. She said, “That’s a thumbnail of the bill, Mr. Chairman.”

The bill covers so many facets of health care, and after seeing so little controversial debate in Senate committee hearings and on the floor, it brought to mind the famous Nancy Pelosi comment about Obamacare: “(Congress) has to pass the bill so you can find out what’s in it.”

Apparently, Florida’s 38 Republican and Senate Democrats took whatever was in the bill on good faith. In three Senate hearings, not one senator raised an objection to the amount of money the bill’s provisions will require.

Price tag: $716 million. No questions asked about money, the Senate adopted the bill unanimously.

Fifteen minutes later, it adopted a related SB 7018. This one establishes a loan fund for Florida entrepreneurs who create money-saving, innovative or technology-driven health care products and services. Price tag: another $50 million.

From the beginning, Passidomo told everyone that expanding Medicaid was off the table. The three overarching objectives were persuasive and convincing. As Burton explained:

In other words, the State would intervene in the marketplace to effect certain results.

How does Florida — or any state, for that matter — increase its supply of doctors, dentists, nurses and mental health practitioners?

The simple answer is: Lower the costs and barriers to entry. Lower the education requirements and time to become a practitioner. Create a framework and climate that makes it easier and less expensive in Florida than elsewhere to become a doctor, dentist, physician assistant, nurse practitioner or nurse.

It’s always a matter of tradeoffs. In this case, Florida lawmakers opted for spending taxpayer dollars and crafting favorable regulatory incentives.

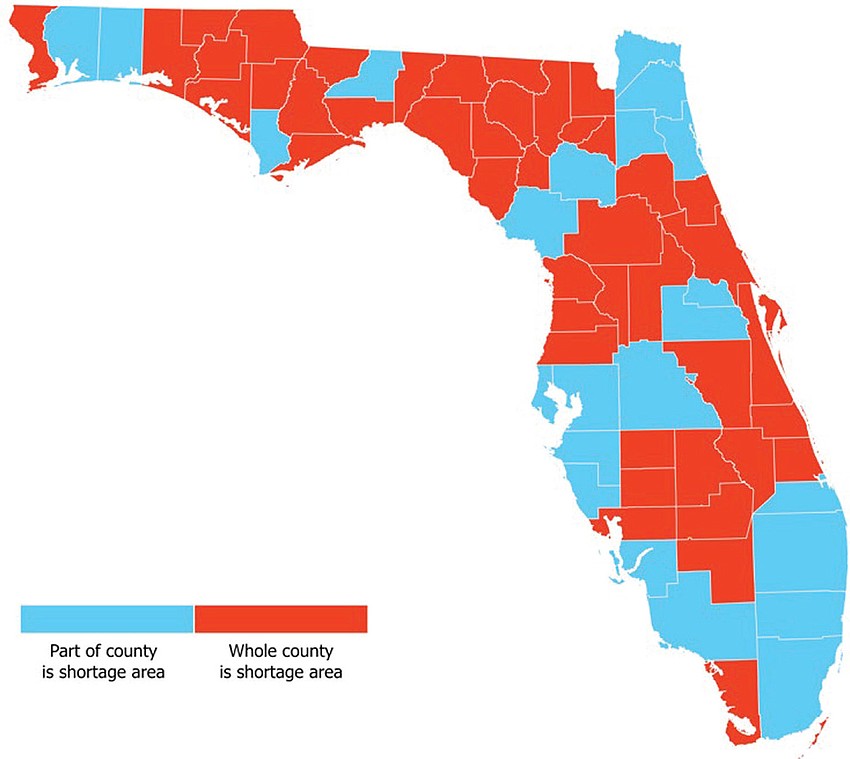

They chose to have Florida taxpayers contribute $38 million to pay off portions of medical education loans in exchange for practicing in a medically underserved area.

Over four years, taxpayers would pay: Up to $150,000 each for medical or osteopathic doctors; up to $90,000 for autonomous APRNs (advanced practice registered nurses); up to $75,000 for APRNs and PAs (physician assistants); up to $75,000 for mental health professionals (clinical social workers, marriage and family therapists, mental health counselors and psychologists); and up to $45,000 for RNs (registered nurses) and LPNs (licensed practical nurses).

Dentists could be awarded up to $50,000 in loan repayment, provided the dentists serve Medicaid and low-income patients and locate in a medically underserved area. Dental hygienists would be eligible to receive up to $7,500 per year for four years.

All recipients would be required to provide 25 hours of volunteer health services.

In 2023, the state received 3,702 applications for loan reimbursements, with 2,774 accepted. The demand is there.

In addition, the Live Healthy bill appropriates $50 million to pay hospitals for 500 physicians to complete their residencies in Florida. It also expands residency programs beyond hospitals into other sanctioned clinical settings.

Heretofore, the federal Medicare and Medicaid programs paid for residencies. But that funding has fallen far short of what is needed in every state, limiting the number of practitioners who can become licensed. Studies have shown more residencies would pay off. The retention rate for medical students who graduate from Florida medical schools and do their residencies here is 75%.

Perhaps the least costly provisions in the bill are reducing the steps for foreign-trained and accredited physicians and graduate assistant physicians to become licensed here. Similarly, the bill allows Florida to join interstate medical licensing compacts for physicians; audiologists, speech pathologists; and physical therapists. This allows licensed practitioners in those states to practice here, eliminating an obstacle.

Altogether, the measures detailed above are likely to increase the supply of medical practitioners in Florida. But at the same time, in lawmakers’ compulsion to be altruistic, the Live Healthy bill includes a provision that is likely to fuel the demand side and cost to taxpayers for medical services. The bill increases the eligibility for free medical care at state sanctioned charitable and free clinics from 200% to 300% of the federal poverty level.

Absent from the bill is a specific appropriation for the increase in free care.

No one knows how these measures will work.

As of press time, the House was still considering its version of the Live Healthy Act. The House version has pared the bill’s cost to $548 million. The final bill’s cost likely will fall in between, while the content of the bill is expected to stay intact.

Either way, $716 million or $548 million seems like a lot of taxpayer money. It is, and it isn’t. Florida’s annual cost of Medicaid is $15.87 billion, with the federal government contributing another $19.8 billion — $35.7 billion altogether.

On top of that, another $10 billion in the state budget goes toward other human services. Altogether, that’s $46 billion in taxpayer dollars, 40% of the state budget, paying for Floridians’ medical care and other social services.

That makes Passidomo’s $716 million look like spritzing a big oak to make it grow more branches.

As noted, making laws is all about incentives and tradeoffs. What we don’t know is how many more practitioners Live Healthy will attract or whether it will become another healthcare subsidy that grows and grows and grows. Passidomo’s bill essentially is adding more money to many existing subsidies.

Nevertheless, give the Senate president credit for attempting to increase the supply of practitioners and not expanding the demand side via the black hole of Medicaid.