- July 8, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

One acre of seagrass can provide habitat for up to 40,000 fish, according to the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, and that same acre of seagrass can also offset the carbon emissions from one car's annual travel by absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

Multiply that by 10 and that’s the estimated impact of 10 acres of seagrass, the acreage that Longboat Key may be required to mitigate as a part of two upcoming, necessary projects.

Longboat's projects — canal dredging and subaqueous force main replacement — are in the town staff’s sights to get underway in fiscal year 2025. Specifically, the subaqueous force main is one that can’t wait any longer, and the town will need to take on debt to get the project underway.

Both of these projects, however, will require dredging the bottom of the recovering Sarasota Bay. Sarasota Bay's water quality is the best it has been in nearly eight years, according to the Executive Director of the Sarasota Bay Estuary Program Dave Tomasko.

Though the recent increase in seagrasses wasn’t caused by planting or mitigation projects, Tomasko said wastewater and stormwater projects are creating conditions good enough for seagrass mitigation projects to take root.

Tomasko is eagerly waiting for the new seagrass maps from the Southwest Florida Water Management District. The aerial photography was shot in 2024, but Tomasko said it will take until 2025 for the agency to interpret the images and deliver the official word.

Tomasko is hopeful. He expects the report to validate his guess that hundreds of areas of seagrasses have recovered in recent years.

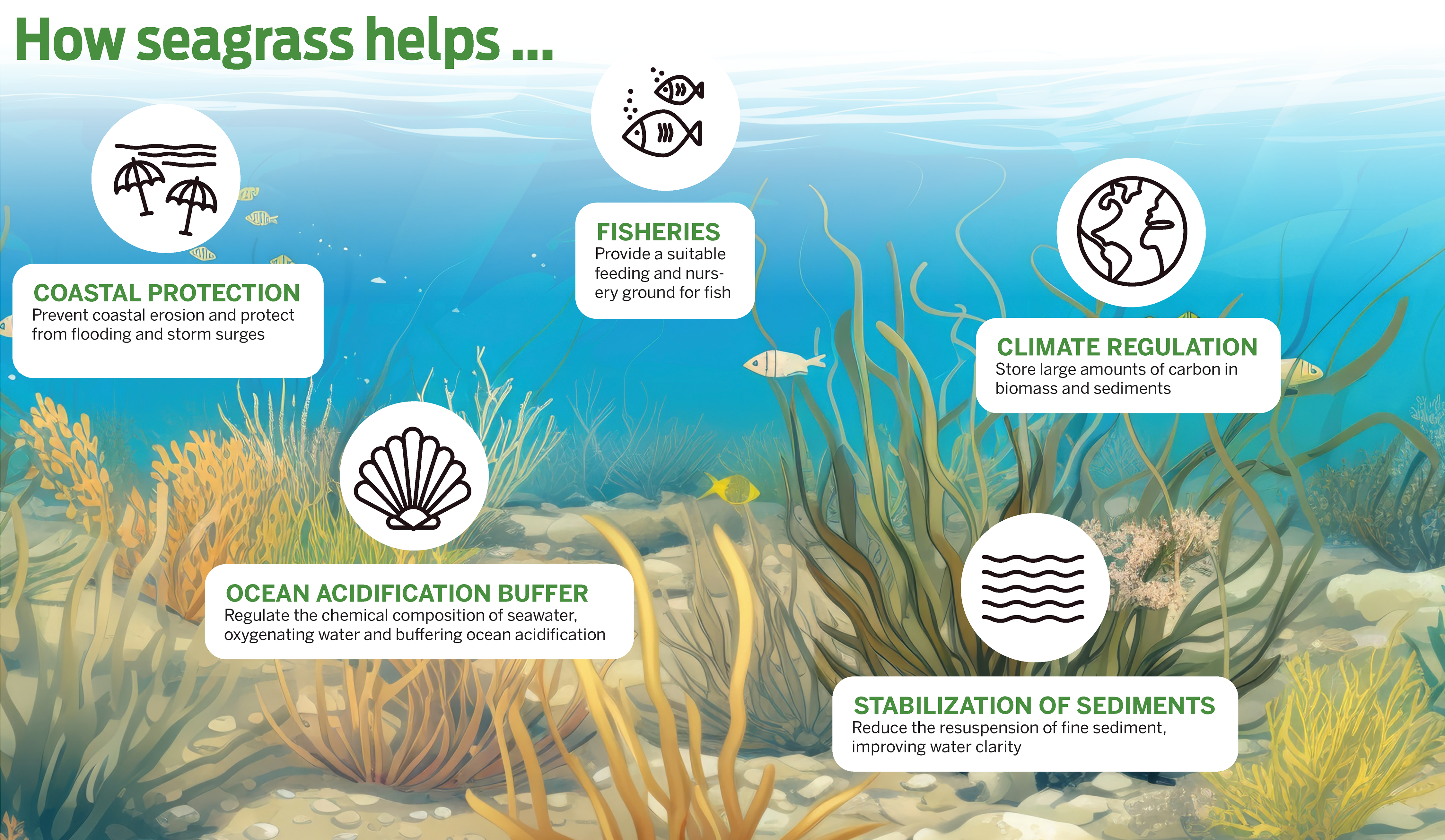

Seagrasses are important marine ecosystems that support organisms like fish, urchins, sea turtles and manatees. Two of the most common Florida seagrass species — turtle grass and manatee grass — reflect seagrass' importance to these marine animals.

“This high level of production and biodiversity has led to the view that seagrass communities are the marine equivalent of tropical rainforests,” said an article from the FWC.

A single acre of seagrass can support as many as 40,000 fish, according to the FWC. Tomasko said that could be juvenile game fish or smaller fish that become food for larger organisms and support the ecosystem at large.

Seagrass meadows are also important blue carbon sources, which means the organisms absorb carbon dioxide emissions from the atmosphere. Tomasko said some studies estimate an acre of seagrass can offset a typical car’s carbon dioxide emissions in a year.

This characteristic also helps offset the impacts of ocean acidification.

“Ocean acidification is not good. It is happening, we’re seeing evidence of it,” Tomasko said. “And seagrass meadows can offset that as well.”

Ocean acidification occurs when carbon dioxide reacts with water molecules to create carbonic acid, which lowers the pH of the water. A lower pH means more acidic water, which spells trouble for coral reefs and juvenile filter feeders.

With seagrasses proven to be important marine ecosystems, Tomasko said about $20 million has been allocated by the state for seagrass transplanting projects. While transplanting projects have value, Tomasko said planting projects shouldn’t become a red herring.

“My guess is we’re going to see hundreds of acres of seagrass come back when the (2025) maps come out, and we’re not planting any of it,” Tomasko said. “Reduce your pollutant loads, get your water quality to recover and the seagrass comes back by itself.”

Seagrass growth corresponds directly with water quality, which also impacts available sunlight. Tomasko said the cleaner and clearer the water, the more sunlight that can shine through to the ocean floor.

That's why, before thinking about transplanting projects, Tomasko said it's important to focus on projects that help overall water quality.

Total nitrogen and dissolved inorganic nitrogen are two products of stormwater runoff that can affect seagrasses. Too much nitrogen can be problematic for seagrass growth and could promote the growth of algae, which blocks light, according to a 2000 study.

To improve water quality, money is better spent on wastewater and stormwater improvement projects, according to Tomasko. One of his Director’s Notes from June 5 stated that local governments have committed to $400 million in projects in the next five years, and $950 million in the next 10 years.

An example is the Bobby Jones Golf Course project, which will convert half of the course to use a regional stormwater retrofit project. This will retain stormwater flows in a treatment wetland for about two weeks to reduce nitrogen loads before flowing downstream.

With water quality on the uptick and local governments committed to stormwater and wastewater projects, the underlying problems are on their way to being addressed. Tomasko said there’s a reason some seagrass isn’t growing in some areas: because these issues aren’t handled first.

Longboat Key needs a new subaqueous force main pipe. The pipe runs under Sarasota Bay, and the mainland portion of the pipe was the cause of a 2020 sewage leak. The mainland replacement was completed in 2023, but new construction estimates for the underwater portion are close to $30 million.

For this project, the town is required by the Florida Department of Environmental Protection and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to undertake 8 acres of seagrass mitigation. That’s according to a memo from the Director of Public Works Isaac Brownman for a June 28 meeting.

No estimate of cost was given by the town department before publication.

Another upcoming project is the dredging of some Longboat canals to get the conditions back to baseline. The last time the canals were maintained was about 20 years ago, according to town staff. About $500,000 will be used in the upcoming fiscal year to get the project underway, but additional funding will be required the following year.

The canal dredging will require almost 2 acres of seagrass mitigation and early estimates price the mitigation at $3.8 million.

Mitigation can be costly, especially since the town’s role isn’t over after the seagrass is planted. Jenna Phillips with coastal engineering firm Cummins Cederberg attended a June 17 commission meeting and said it’s easier to have one large mitigation area rather than small ones scattered all over the bay.

“Regardless of where you mitigate, you’re going to be required to maintain it in perpetuity. So that becomes really difficult when you start doing a little bit in a lot of different areas,” Phillips said.

Conditions for seagrass mitigation projects have to be near perfect, mainly regarding depth. Luckily, the town already has a permitted spot — an old pipe scar and an abandoned Intracoastal Waterway located off the coast of Joan M. Durante Park.

A seagrass mitigation project like this will first require sand to fill those dredged areas to a level where light can sufficiently penetrate the ocean surface.

“Any part of the bay that’s deeper than say 6 feet is going to have a little bit of a hard time supporting seagrass,” Tomasko said.

After sand fills in those areas to a depth where light can reach the bottom, a little bit of seagrass planting can go a long way.

“Take some of the seagrass that’s going to be pulled out and damaged and put it into the footprint of the pipeline that’s been raised to become a little shallower, and you may actually have a really good project,” Tomasko said.

Tomasko added that the SBEP already has a solid relationship with the Town of Longboat Key, and the organization is ready to assist with these future projects. If all goes well, the improved wastewater pipe and seagrass mitigation projects could be another good project for bay health.

“We know how important that pipeline is, but we also know that it’s going to be a destructive activity that has to be mitigated,” Tomasko said. “And if it’s done correctly, it could be a net positive for the bay.”