- November 13, 2025

-

-

Loading

New surveys of Longboat Key’s canals provided updated information on what work is needed to get the canals back to the permitted design, or baseline. It's been 20 years since Longboat’s last canal dredging project.

As Town Manager Howard Tipton described, the new estimate shows a “reduced scope” with a large cost difference, from the original estimate of $16.8 million to now $9.25 million for the initial work.

In November 2023, Assistant Director of Public Works Charlie Mopps presented a draft of a canal maintenance program, including the $16.8 million initial dredge project that would re-baseline the canals. He was joined by Taylor Engineering, Inc., which used canal surveys from 2017.

That presentation left commissioners more confused than confident, and Mopps was directed to figure out ways to cut costs. That’s when he suggested a resurvey, which was presented recently at the June 17 commission workshop.

“One of the things that we did discuss was going back and doing a resurvey, getting some real numbers out there to kind of really justify where the value of this program would be,” Mopps said.

Mopps brought in First Line Coastal to conduct the new surveys and move the canal dredging program forward.

The previous estimate was based on 2017 data and estimated that the dredge would be about 127,000 cubic yards across 96 waterways. The cost for just the dredge was $12 million.

“Those numbers were based on a number of critical assumptions along the way, and those assumptions have now been updated with the results of the new survey,” said Mark Stroik with First Line Coastal.

Stroik and his team implemented an investigatory-style survey, which Stroik described as “fast and economical.” He said it’s extremely accurate in the coverage areas, though it does come with blind spots. The blind spots could be created by things like obstacles — docks or mangroves — that block the readings.

To address the blindspots, the First Line team had to simulate some of the data using 3D modeling, which created a model of the entire canal.

Stroik and his team took a boat down every one of Longboat’s 96 canals to conduct the surveys and see for themselves the status of the canals.

Of the 96 canals, 72 have a permit and design history and 24 do not.

Aside from the modeling, Stroik’s team assessed the canals based on a variety of navigability factors, including maneuvering, docking, common vessels on Longboat Key, impediments and environmental exposures.

“I must say, having personally driven down each one of your canals, I thought it would be worse than it was,” Stroik said.

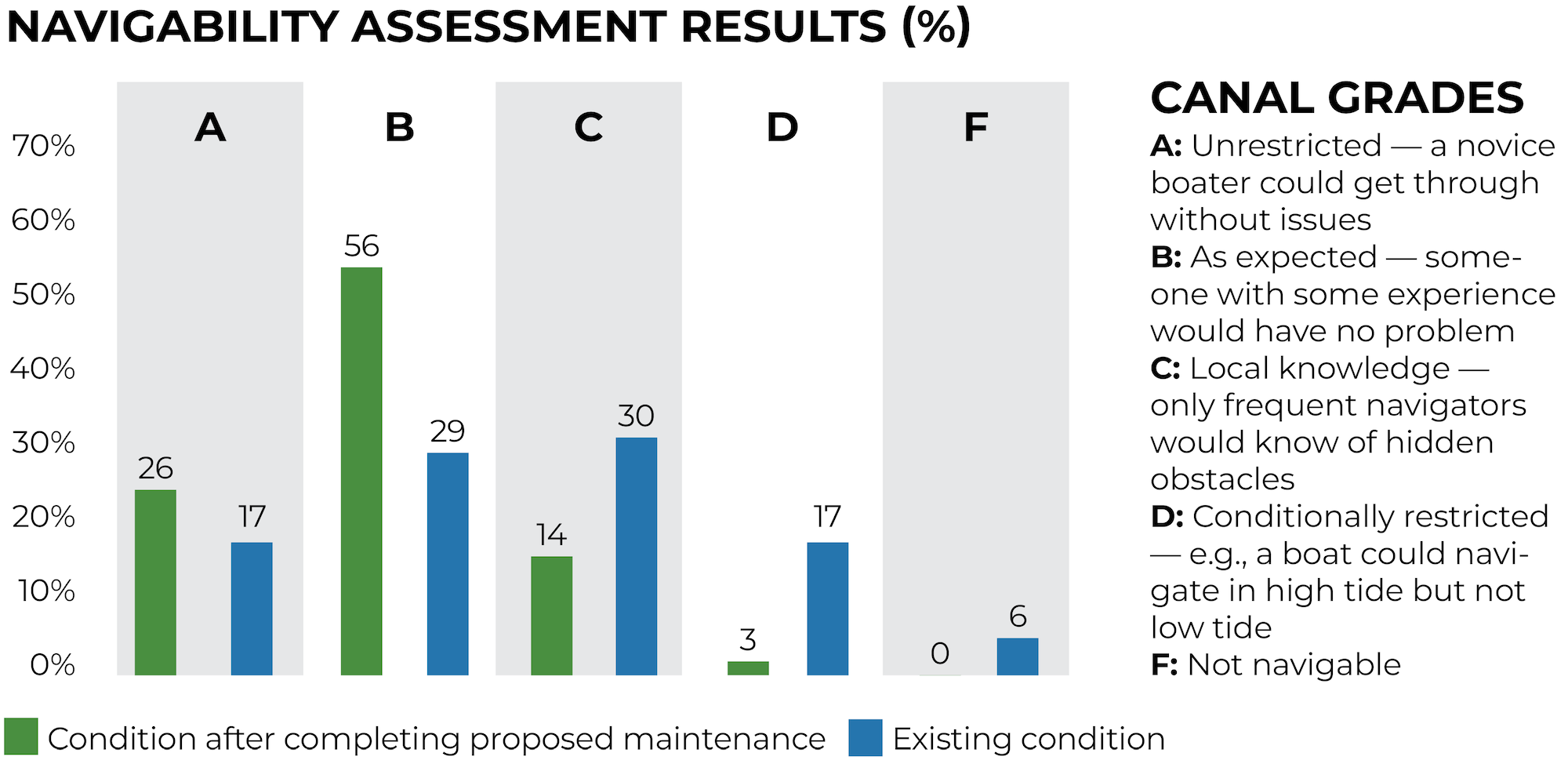

First Line used a grading system similar to a grade school report card. Canals graded “A” means the canals are in good condition with no restrictions, whereas canals graded “F” are not navigable.

From there, the canals were given values based on their current condition, as well as what condition each could be in if it was dredged as part of the maintenance program. Aside from just the depth of the canals, other factors like overgrown mangroves are also taken into account.

For example, a canal could be given a “C” grade with its current condition, but Stroik’s assessment also would show that the same canal could be a “B+” if it was maintained.

Most of the town's canals are in the "C" range, Stroik said, which means only those with local knowledge could safely navigate them.

With updated data in hand, Stroik and Mopps told commissioners that not all of Longboat’s canals need the same amount of work, and some don’t need any work at all.

Of the 96, the team estimated that 48 of the canals wouldn’t require dredging. On top of that, 7 were recommended to be removed due to not being used or leading to nowhere.

In 71 of the canals, the team fine-tuned the scope of the dredging by removing non-productive dredging. It’s not reasonable to chase inches in projects like this, Stroik described.

This new data led to the estimate that an initial dredge would be around 40,000 cubic yards and cost about $3.68 million for the dredge portion.

In total, the new estimate for the baseline dredge is around $9.25 million.

Other costs aside from the dredging are permitting, design, management and seagrass mitigation, as well as adjusting for inflation.

The seagrass mitigation is required since certain canals have seagrasses that would be impacted by the dredging. When Mopps originally presented it to the commission in 2023, the estimate for mitigation was $1 million. Now, it’s around $3.6 million.

Originally, Tipton and staff recommended assessing a 0.0570 millage to generate $500,000 to kickstart the program starting in FY25.

Vice Mayor Mike Haycock, though, expressed concern over imposing the millage without adequate public outreach.

The commission reached a consensus that no millage for the canal program would be imposed this fiscal year, and that staff would look for the $500,000 in other areas of the budget — possibly in reserves — to keep the ball rolling on the project.

Tipton said staff will return to the commission in the fall to further discuss the funding method.