- January 22, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

Is water quality the only indicator of a healthy ecosystem? Not quite.

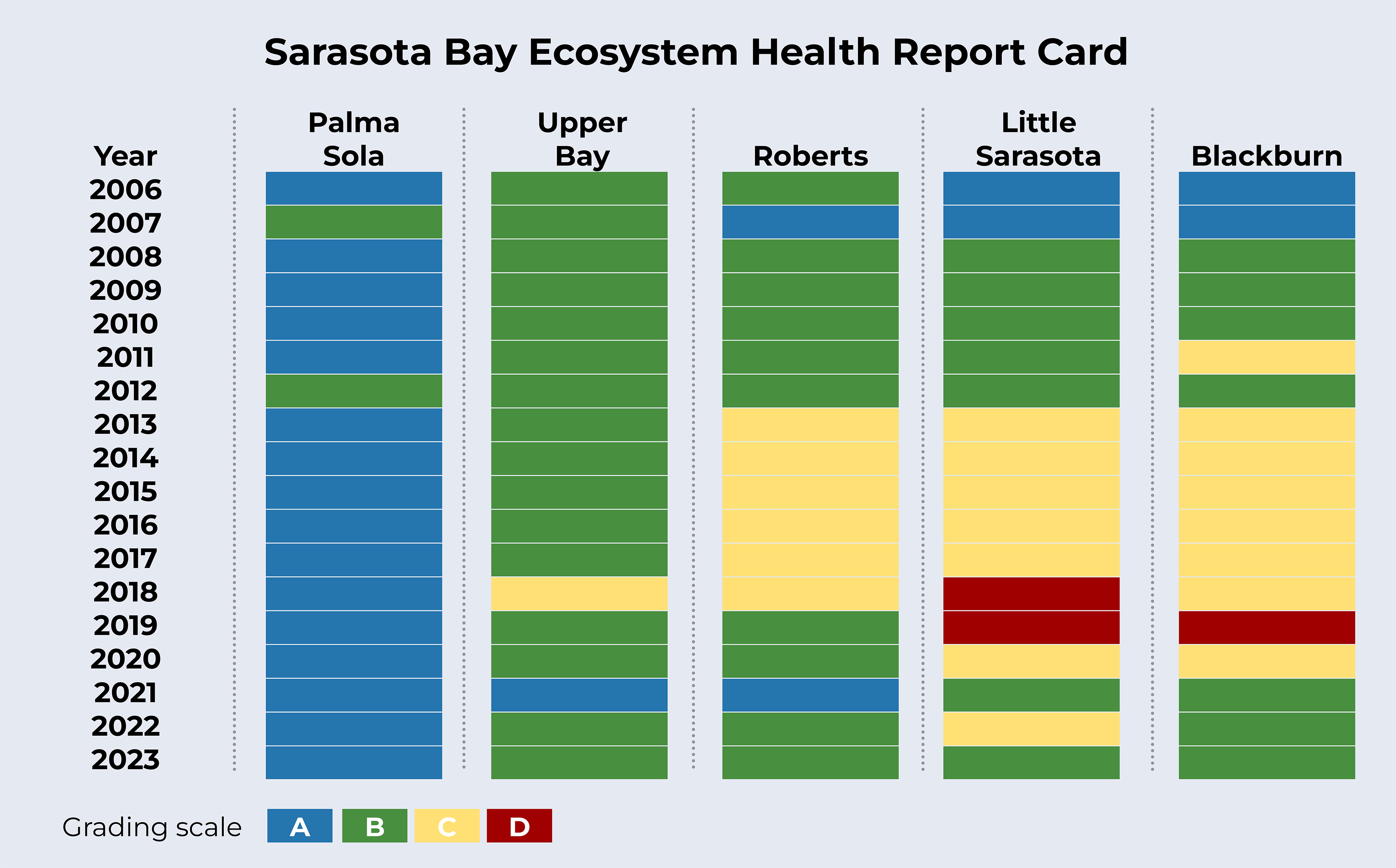

The Sarasota Bay Estuary Program recently published its 2023 Ecosystem Health Report Card, which showed that all bays in the area are in good standing with their ecosystem health. The chart also shows a larger trend of the bays, from a period of stability to a decline, back to now a recovery.

Dave Tomasko, executive director for SBEP, said that water quality is one factor in determining ecosystem health, but there's more to consider.

“People use the words water quality and ecosystem health like they’re the same thing, and they’re not,” Tomasko said.

Water quality is like dipping a bottle into the bay and looking at what's in it, he said. But looking at the full picture requires looking at data about nitrogen, chlorophyll, seagrasses and macroalgae.

Macroalgae are the large seaweeds that commonly grow on the bottom of the bay or found floating. Those plants are valuable food sources for animals like manatees and sea turtles.

But when macroalgae blooms occur, it decreases the amount of oxygen in the water which is harmful for marine life.

“If we don’t collect this information, we’re going to miss one of the big problems,” Tomasko said.

Tomasko said the SBEP came up with the idea for the Ecosystem Health Report Card around 2021, and were able to use historical data to create the chart going back to 2006.

On the chart, there are three time periods that Tomasko pointed out.

From 2006 to 2012, the ecosystem health of the bay was good and stable. Then, in 2013, a period of decline started which went until about 2019. Since 2020, the bay has been recovering, leading to the 2023 report that shows a good bill of health.

Seagrass is another one of the ecosystem health components, and the data of seagrass coverage fortifies the time periods Tomasko outlined.

Before 2013, there was about a 28% increase in seagrass coverage, according to Tomasko. In the decline period from 2013-2019, there was about a 30% loss in coverage. Then, a steady increase in the last couple years.

Now, the SBEP is waiting to get updated seagrass maps. Aerial images and surveys were recently completed, but the SBEP won’t get the results back until 2025.

Based on his own observations and hopes, Tomasko said he has a personal estimate of 800 acres of added seagrass in the survey.

“Seagrass is an indicator of a healthy system, and I think it’s going to be a big increase,” Tomasko said. “I think it’s going to be the biggest increase we’ve had in more than a decade.”

Nitrogen is also an ecosystem health indicator and, like macroalgae, there’s a fine line between “good” levels and too much. At stable levels, it’s an important nutrient for all marine life. But if there’s too much, algae blooms can occur.

Tomasko said the nitrogen levels have been good, and estimated the numbers are at the lowest in the past 15 years.

Stormwater and wastewater are common contributors to high nitrogen levels. Previous years’ yellow, or “concern,” reports were caused in part by wastewater. Tomasko said while some facilities were doing well with about 95% of wastewater, the 5% was enough to set the bay back in that period of decline.

“And that’s the thing with wastewater, it’s more damaging than stormwater,” Tomasko said.

Wastewater systems have been mostly fixed since then, he said.

In 2021, the Palma Sola Bay, Upper Bay and Roberts Bay all received an A grade on the report card. Little Sarasota Bay and Blackburn Bay got Bs, which are still good.

Then, in 2022, Little Sarasota Bay dropped to yellow, or a C grade. That indicates there’s an area of concern.

Tomasko said that dip was because of Hurricane Ian, and Little Sarasota Bay was one of the bays most impacted by the storm. Since then, Little Sarasota Bay has recovered to a B grade.

In 2023, Palma Sola Bay continued to be one of the healthiest, and maintained an A, indicated by the blue. All other bays were green, with a B grade.

The SBEP was also recently asked to join an organization called the Agency on Bay Management.

The ABM is a natural resources committee of the Tampa Bay Regional Planning Council. The committee brings together other organizations to encourage conversations and collaborations between the stakeholders involved in the protection and use of the region’s waterways.

Tomasko said he received an invite to join the ABM about three weeks ago. The SBEP was never a part of the agency before.

The new partnership costs nothing for the SBEP, and allows the SBEP to collaborate more with other agencies in Tampa Bay. There’s also more opportunities for peer review on approaches to management.

Sharing the approaches and data is important, since some issues between Tampa Bay and Sarasota Bay overlap.

For example, after the Piney Point incident in 2021, the SBEP collected macroalgae data in places further north like Holmes Beach — technically outside of their normal range.

Though the Piney Point spill happened in Tampa Bay, there were negative impacts further down.

“It’s kind of the opposite of Las Vegas, like ‘what happens in Vegas, stays in Vegas,’” Tomasko said. “What happens in Tampa Bay doesn’t stay in Tampa Bay.”

In the future, Tomasko hopes that, through this partnership, the SBEP can share their approaches and success stories with agencies in Tampa Bay, and vice versa.

He said this will be important in the coming years, as Sarasota County continues to try to reestablish a connection between Little Sarasota Bay and the Gulf of Mexico. In Tampa Bay, there have been several tidal restoration projects that Tomasko said he hopes to learn from.

“We get to talk to them about improving our water quality, and we get to learn from them a little bit about how they did the tidal restoration,” he said.