- April 30, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

With thousands of residents impacted by Hurricanes Helene and Milton across Longboat Key and Sarasota County, the area is a flurry of construction activity.

For some residents, it means repairing roofs, windows and storm shutters. For others, it’s a total rebuild.

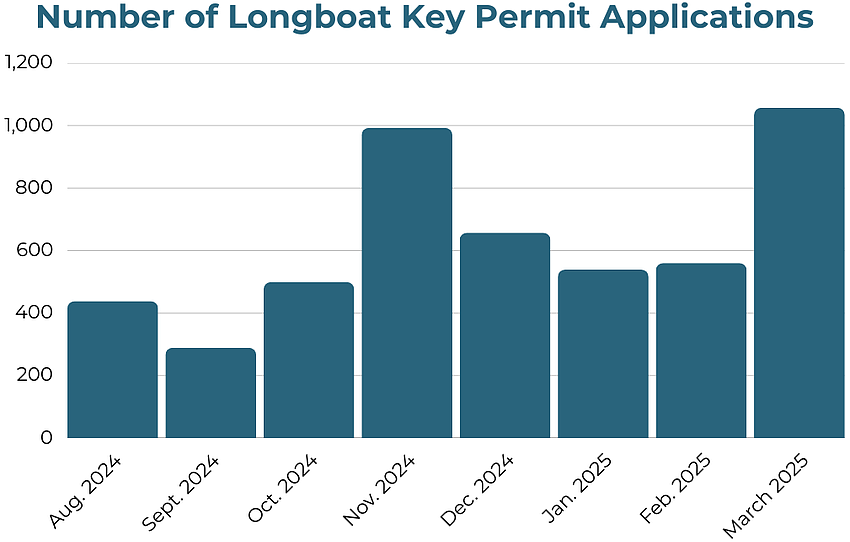

The increased activity shows up through the planning departments of Longboat Key, the city of Sarasota and Sarasota County. Longboat Key, for example, estimates permitting activity is double what it was this time last year, with 1,057 permit applications received in March.

On the island, homebuilding is changing in the wake of Hurricane Helene, which brought a devastating storm surge to areas like the Village, Sleepy Lagoon and Buttonwood Harbour.

Longboat Key resident Heather Rippy and her family are among those who experienced flooding during Helene and now need to make major repairs — the most substantial of which is raising the house 12 feet.

Rippy owns Driftwood Beach Home and Garden in Whitney Plaza, and the family lives in one of the original Whitney cottages built in 1937 in Longboat Key’s Village.

Although the storm didn’t destroy the house, it sustained about two-and-a-half feet of flooding.

Rippy said Helene was the first time they had water in the house. In previous storms, water collected in low parts of the yard, which is normal for living in one of the island’s lowest areas.

“We kind of expected that to happen again, but we really didn’t expect to get two-and-a-half feet inside the house,” Rippy said. “That was devastating.”

Flooding destroyed the family’s furniture, and the house needs a complete interior remodel. But when going into the repairs, the Rippys wanted to maintain the historic feel on the outside and preserve the house as much as possible.

“It’s an old house on the outside, and it will be a brand new house on the inside,” Rippy said.

The family planned on raising the house before the 2024 hurricane season, but a delay with their contractor caused them to miss the May 2024 start goal.

That meant they had plans ready, though, so after Helene, they quickly started the process of raising their historic house in November 2024.

Rippy and her family aren’t yet able to live in their home.

The bulk of the raising work is complete, and the house now sits about 12 feet higher. The interior work remains, Rippy said, including new finishes and extending plumbing and electrical to the new height.

She said they’re hoping to move into the house in June.

Some residents are starting from scratch.

Down the road from Rippy, Village resident Eddie Abrams’ property is an empty lot, as is his son’s next door.

During Helene, the homes took on 48 to 60 inches of water, depending on where they measured.

“We tore them down and we’re going to try to rebuild. That’s the hope, anyway,” Abrams said.

The homes sustained enough damage that repairs would tip well over 50% of the value of the home, Abrams said, which means the home has to be brought up to code per the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s 50% rule.

Abrams has plans in hand to build a new house and will make sure the next house is well-elevated. His son, Grant, will do the same with his house.

“We want to build as high as we can by code,” Abrams said.

Last summer, the Longboat Key Town Commission adopted new ordinances to increase the freeboard allowance for homes. The ordinance progressed to allow homes in low-lying areas to add up to an extra 4 feet of freeboard on top of the 1 foot already required.

Abrams’ previous home was about 2.5 to 3 feet above grade, he said, so adding the additional 5 feet of freeboard will bring the home around 8 feet above grade.

Not only is Abrams building higher, he’s building a more fortified house, he hopes.

He’s opting to use a technique called Insulated Concrete Forms. He explained it simply as “a Styrofoam form you put together like Lego blocks.”

Rebar reinforces the blocks and filled with concrete. Exterior finishes apply directly to the Styrofoam-type forms.

Abrams said his family heard about ICF online and had seen it on television programs. When they purchased their home, they were aware of its low elevation and kept ICF in mind as a method of creating a more resilient house.

“It’ll be a concrete bunker,” Abrams said.

Abrams is also a do-it-yourself resident and decided to go with an owner-build construction. He will bring on licensed contractors, such as a general contractor, to oversee the project, but Abrams plans to be as hands-on as the state building code permits.

By overseeing the project, Abrams said there may be some cost savings in terms of choosing certain materials or methods.

Abrams and his family are still piecing together pricing for the rebuild and looking into how to fund it through methods like grants.

“The insurance was disappointing, to say the least,” Abrams said.

Progress has been slower for others, like Adam Gersh in Sarasota. Gersh, like Abrams, is dissatisfied with insurance responses.

Although across the street from bay front homes, the bulk of the damage to Gersh’s elevated home in Sarasota’s Harbor Acres was wind, not flooding, from Hurricane Milton.

Ever since, he and his wife, Wende, have been attempting to secure an insurance settlement for a roof replacement. Contractors have said because of the location of the damaged tiles, the entire roof should need replacing. Gersh has singled out insurance carrier Monarch as the obstacle to affecting his repairs six months after Hurricane Milton.

“We had to go to what we call appraisal, so they denied the claim,” Gersh said. “It’s really, I think, a bigger issue because everybody I’ve talked to, nine out of 10 times, this is the issue. Monarch Insurance is the company that I’m dealing with, but other companies have the same MO, and this is how they operate. That’s really the main struggle. It’s not finding qualified individuals to do the job, which I thought would be very difficult.”

Abrams is still uncertain exactly how much his rebuild will cost, but said the majority of the costs would be in the concrete used to fill in the ICF blocks.

Going with owner-build also helps Abrams slightly evade the challenge of finding subcontractors, which he’s heard is difficult for some people.

“We’re hearing from our general contractor that it’s been challenging ... especially locally, the subcontractors are very busy right now,” Abrams said.

With plans in hand, Abrams and his son will head toward the permitting process in the coming weeks — a process that is crowded with hundreds of other residents trying to do the same.

The town of Longboat Key’s Planning, Zoning and Building Department received its own surge — a surge of building permits.

“I would say we’re probably at double the amount of permitting we would normally see. And we also have certain new responsibilities post-hurricane,” said Allen Parsons, the department’s director.

Those additional responsibilities include conducting a substantial damage determination for properties that request it, adding extra work for town staff. Homeowners may request the determination for grants or other applications.

The overload of work led to the need for extra hands around the department.

Parsons said the department received extra staff through the Florida Department of Emergency Management immediately after the storms, as well as more contracted help along the way.

“Over time, we’ve been able to build up and supplement our staff both through FDEM and then through private contracting,” Parsons said. “We’re now about double the size of our full-time staff.”

The 12 new staff range from plans examiners to inspectors to help the department deal with the influx of permits for storm-related repairs.

The town alleviated some burden on property owners through fee waivers and construction hour extensions.

Sarasota County is experiencing similar needs for supplemental staff, as well as the complexity of certain storm-related permits.

Michael Deming, a building official with the county, explained the unique scenarios posed by the damage done to condominiums.

“What we were seeing were people or groups coming to us who were being hired by the condominium associations to do work of a limited scope that was being paid for directly by the condominium associations and not by the individual unit owners,” Deming said. “We shifted in those instances to develop a process to allow them to apply for multiple units that were having identical work done by the same contractor, to include those multiple units under one permit. That way, it didn’t require each of the individual unit owners to have to pull permits when they weren’t the ones actually having the work being performed.”

The complication, and the need for a secondary permit, arose because, in some instances, the first permit was not for work that returned the individual units to a habitable state. The permits went as far as tearing out and replacing drywall, but did not include any interior finishing work.

“We had to follow up with contractors, with condominium associations and with the individual unit owners that, in those instances there would be a requirement for a secondary permit so that we could verify the unit was returned to its full habitable condition,” Deming said.

Since Hurricane Debby wreaked much of its damage inland in August, the county has received just more than 6,000 permits countywide that were specifically notated as storm-related damage. Of that number, Deming said, 82% of them are approved. That doesn’t include the permit applications received for new construction and nonstorm-related renovation projects.

The county typically has two floodplain reviewers on staff. To help serve the hurricane-related permit application volume, the building department mobilized the eight building review staff members to assist with flood reviews, working overtime, plus state-funded contract personnel.

According to Parsons, the Longboat Key department has a three to seven-day turnaround for simple permits for various repairs, but larger permits like a single-family home reconstruction may take up to three weeks.

A meticulous review of permits is essential, especially when dealing with properties that were substantially damaged.

“We’re audited by FEMA to ensure that we’re not issuing permits for work that would exceed that 50% value,” Parsons said.

It’s because of that audit that staff need to review permit applications closely. Any discrepancies could cause permit delays.

Regarding other delays, Parsons said he has heard of some cases of miscommunication between contractors and property owners.

“In some cases, permits haven’t been submitted, and in other cases, they’ve been submitted recently and issued,” Parsons said. “So there may be some misunderstandings out there of when a permit has actually been submitted to the town.”

However, the Longboat Key department recently announced a new online permitting software, which will activate on April 22.

The software is designed to create a deeper connection to the public, including a GIS map interface, and will allow property owners to conduct permit applications online.

“The move will provide a standardized, cloud-based solution that will provide better service to customers, the public and staff,” the town said in a statement.

On St. Armands Circle and the mainland, residents are feeling the pressure of permits.

St. Armands Residents Association President Chris Goglia said homeowners who are restoring or rebuilding have reported frustrations in the amount of time the city of Sarasota is taking to process building permits.

“It sounds to me that people are saying it’s taking a long time. They’ve been waiting for months to get permits,” Goglia said. “People have expressed disappointment that the permitting process is taking so long. They don’t understand why it’s taking so long.”

According to the city, hurricane-related permits were to be noted as such to receive expedited review. To date, the city has received 743 storm-related building permit applications and, out of those, 106 remain under review. The remainder are either issued or inspections are complete and closed.

Applications are still being expedited for review, a spokesperson told the Observer. Fees are waived for those received before April 1.

On Siesta Key, resident and community activist Lourdes Ramirez said it took six weeks for a county staff person to be assigned to review her permit application. Her home was flooded by Helene and suffered further damage from Milton.

“In my case, they said the permit was not labeled as hurricane-related, so it was not on the expedited track,” Ramirez said, adding that once remedied, the application was fast-tracked. “I found it hard to believe that any permit request for Siesta at that time was not hurricane-related.”

Owners of condominiums, she added, were told they needed two permits, and in some cases were told that until all the units were ready, there would be no issuing of further permits.

Harbor Acres resident Gersh doesn’t know about any delays in permitting, primarily because he hasn’t gotten to that point yet.

The next step for Gersh is to retain a public adjuster to present the case to the insurance company, which Gersh said draws out the process even longer and, eventually, homeowners give up.

“I think it’s intentional through attrition,” Gersh said. “When I talked to the public adjuster, he said people just give up. I’m not somebody who gets worn down when I feel like I’m owed. You are going to hear from me until the cows come home, until I feel like it’s resolved. I’m not giving up on it.”

With hurricane season approaching, Gersh said one way or another, his roof will be replaced.

Back on Longboat, Abrams said the town’s staff has been helpful so far.

“I will commend the town of Longboat Key and the staff. They have really been remarkable,” Abrams said. “I just can’t praise them enough.”

As a former engineer himself, Abrams understands the packed schedules of building department staff. That understanding led to a deeper appreciation for how the staff took time to meet with him regarding his plans.

“I know it’s hard to make time for somebody that wants to walk in and look at your plans when you know you have 100 things on your plate to do that day. But they took the time,” Abrams said.

Correction: This article has been updated to state that Michael Deming is a building official with the county.