- July 10, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

“I’m here to see Rick Barry,” I told the guard at the gate.

“Who?” asked the guard, who looked to be about 30.

“Rick Barry. I should be on a list,” I replied.

“Rick Barry? The Rick Barry, the basketball player? He lives here?”

“That’s him.”

After the guard cleared me to enter Lakewood Ranch’s Lakewood National community and just as I was pulling away, he called out, “Can I come with you to the interview?”

I think he was serious.

His reaction surprised me. The name Rick Barry, Basketball Hall of Famer, is more apt to resonate with baby boomers. He’s a bona fide hoops legend, who also made his mark as a TV color analyst. The National Basketball Association named him one of the 50 Greatest Players in NBA History when the league celebrated its half-century anniversary in 1996. Twenty-five years later the league unveiled its 75th Anniversary Team, and Barry was among the 75 players honored.

He also stirred up his share of controversy, both during and after his playing days, and was widely reviled by his peers. His former teammate and friend, Billy Paultz, once said, half-jokingly, “Half the players disliked Rick. The other half hated him.”

Barry is 80 now and spends the winter months in a unit of a quadplex that overlooks Lakewood National’s golf course. Largely because he plays a lot of pickleball at various courts in Lakewood Ranch, Barry gets recognized and approached regularly, mostly by boomers who know him from his basketball days. “People ask me, ‘Don’t you get bothered?’ I say, ‘Hell, at my age it’s nice that people still remember me.’ If I’m not too busy, I’m glad to take a photo with people. I feel honored.”

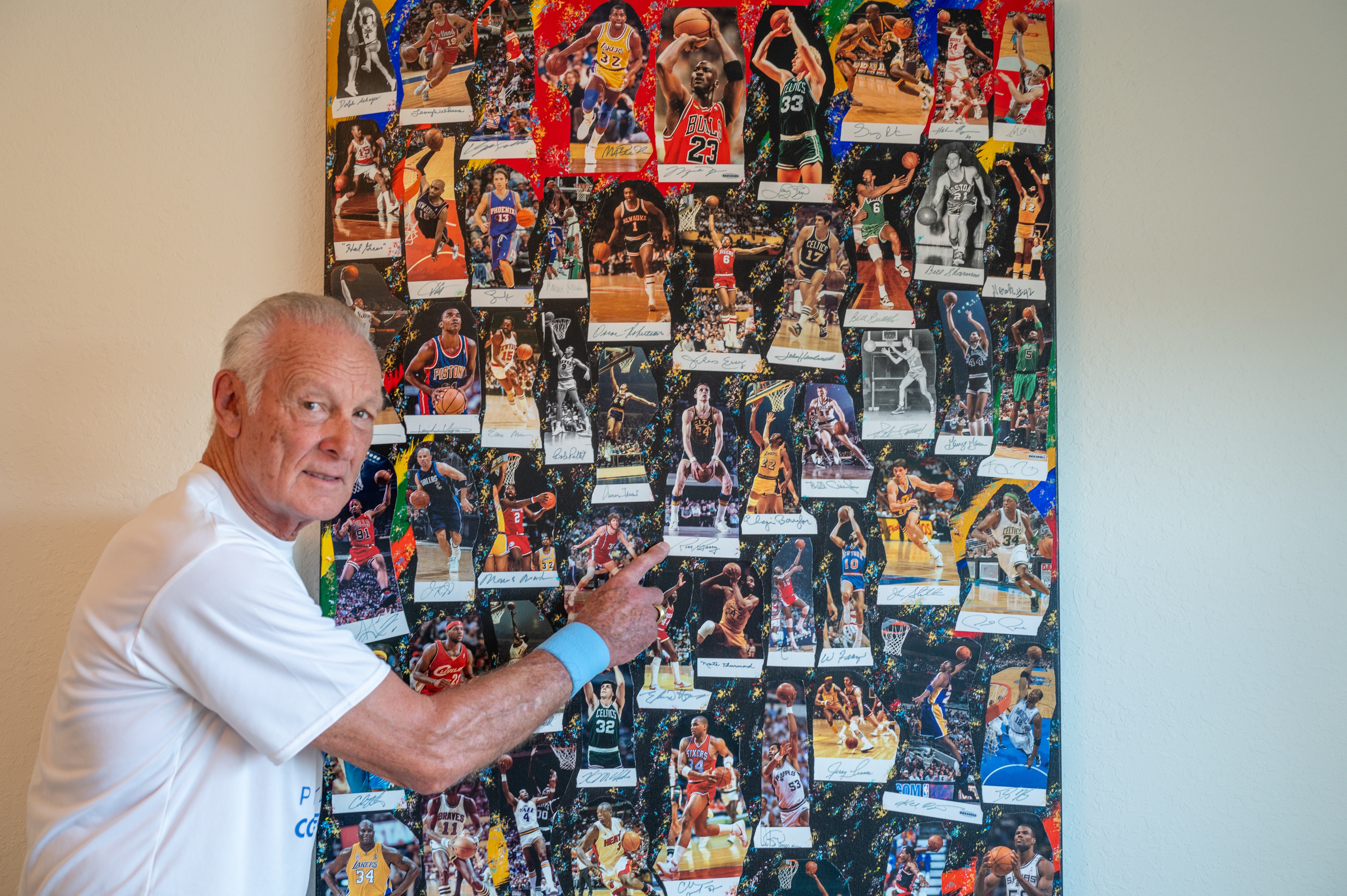

Barry lives with his wife, Lynn, in a home that overlooks the 10th hole. On this hot mid-afternoon in early December, the balcony was roasting in the sun, so Barry suggested the living room for our interview.

He’s still a lanky 6-foot-7. His body has all of its original joints, which is saying something when you consider his age and the pounding his body took during a 15-year pro career. His knees aren’t in great shape and his back gives him trouble, he says, but it’s nothing he can’t overcome with a good stretching routine.

Barry was dressed in monochrome — royal blue shorts, Crocs and a T-shirt representing the Golden State Warriors, the team he played for most of his career and led to an NBA Championship in 1975.

Lynn was on her way out to play pickleball. I asked the couple how long they’ve been married.

“Thirty-four years,” she replied.

Barry chimed in. “Yeah, but I count 39, because of the five years of relentless pursuit.” He grinned at his wife, causing her to roll her eyes.

Lynn, 65, was a baller, too. The St. Petersburg native played for William & Mary in Virginia, setting 11 school records in four seasons, two as captain.

The Barrys spend the other half of the year in Colorado Springs, their primary residence for nearly 40 years. They’ve wintered in Lakewood Ranch since 2017. “We wanted to be near her parents once our son Canyon went off to college,” Rick explains. “We visited The Villages, then we heard about Lakewood Ranch. It’s closer to her parents, and closer to airports. And we just liked it here more. I mean, it’s too busy up in The Villages.”

Barry spends his days playing pickleball, riding his bicycle and working out in the neighborhood’s exercise facility. “I’m not super-social,” he says. “We rarely go out to eat. I’d just as soon stay home, make a nice salad, eat healthy.”

Richard Francis Dennis Barry III grew up in Roselle Park in northern New Jersey. His father coached him during his early basketball days, stressing fundamentals. Barry played on the junior high team when he was in the fifth grade. He starred in basketball and baseball in high school, but ultimately focused on hoops, playing games in the park, and drilling when no one was around.

At the urging of his father, Barry switched to using a two-hand, underhand technique to shoot free throws. Despite his myriad achievements and laurels, Barry’s decidedly uncool, “granny” foul-shot style is probably what he’s most noted for. Not for nothing, his NBA free throw percentage was 89.98%, fourth best of all time.

Barry notched a stellar career at Roselle Park High — making All-State twice — but, he says, “I couldn’t stand my coach. He was crazy, always screaming and yelling. I came home one day and told my [older] brother that I wasn’t going to play anymore, and he said, ‘No, you can’t do that. You’re gonna get a scholarship and a chance to get an education.’ My brother and father convinced me not to quit.”

After receiving over 30 scholarship offers, Barry chose the University of Miami for several reasons: he liked the coach, Bruce Hale; he was drawn to the team’s fast-paced style; and, as he puts it, “I didn’t want to be anyplace cold.” Barry later married Hale’s daughter, Pam, and they had four sons, all of whom played pro basketball.

In his three varsity seasons at Miami, Barry averaged 29.8 points and notched five games over 50 points (with no 3-point shot at the time). The school’s Hall of Fame website calls him “the greatest basketball player in University of Miami history.”

The San Francisco Warriors selected Barry second in the 1965 NBA draft. He told me that the team offered him an initial yearly salary of $12,500, which he negotiated up to $15,000, plus a $3,000 signing bonus. “I was as happy as a pig in slop,” Barry says. “Somebody was paying me $18,000 to play basketball.”

He earned Rookie of the Year honors, then in his second season led the league in scoring with a 35.6-per-game average and was named to the All-NBA First Team. (Wilt Chamberlain won MVP.)

Barry was the first athlete in major American professional sports to challenge the onerous “reserve clause,” which gave teams the right to renew a player’s contract automatically, binding him to the franchise and making free agency effectively impossible. The Oakland Oaks of the upstart American Basketball Association made Barry a substantial monetary offer, and promised to bring in Hale, his father-in-law, as head coach.

The Warriors exercised the reserve clause. The courts ruled against Barry and said he would have to sit out the 1967-’68 season to play for the Oaks. Call it stubborn, call it principled, but that’s what Barry did.

Three years later, baseball player Curt Flood filed suit to challenge the reserve clause, and in 1972 the U.S. Supreme Court struck it down in a landmark case. Although Barry gets little credit, he helped open the floodgates that see top NBA stars making in excess of $50 million a year.

With his stats, Barry would certainly command a mega-contract if he were playing today. “It’s hard for me to wrap my head around the idea that I would make $60 million playing basketball, with $300 million guaranteed for five years,” he says, shaking his head and grinning.

Looking back, Barry says, “I don't think I was ever in the top 15 in salaries in the NBA, which I should have been. But I didn't play for the money. From a business standpoint, I was stupid.”

Barry won an ABA championship in his first year with the Oaks and went on to play three more seasons in the struggling league before signing again with the Warriors. The 1974-’75 season marked the pinnacle of his career. In the NBA Finals, Golden State was a heavy underdog to the powerhouse Washington Bullets but won the championship in a four-game sweep. Barry won MVP. “It was the greatest upset in the history of major sports in the United States,” he declares, leaning forward, hands on knees.

That’s classic Barry — sure of his opinions and blunt in delivering them. These traits earned him a reputation as being difficult, and worse. Slate once referred to Barry as “the most arrogant, impossible son of a b— to ever play the game of basketball.” His one-time teammate Mike Dunleavy told the Chicago Tribune, “You could send him to the U.N., and he’d start World War III.”

In 1983, Barry conceded to Sports Illustrated, “I acted like a jerk … I was an easy person to hate. And I can understand that.”

Barry’s unabashed candor didn’t do his broadcasting career any favors. “You’re supposed to be a dumb jock,” he says. “I wasn’t afraid to freaking speak my mind.”

Barry maintains that his penchant for criticizing teams and players — pointing out mistakes in a way that today would be considered anodyne — labeled him as being too negative. “There are good things and bad things that happen in games,” Barry says. “I talked about both of them.”

While working as an analyst during the 1981 NBA Finals, Barry made an offhand reference to his broadcast colleague Bill Russell’s “watermelon grin.” A backlash ensued. Barry claimed not to have known about the remark’s racist overtones and apologized. CBS did not renew his contract for the following year. “If I had said ‘Cheshire cat grin,’ it would’ve been fine,” he says with a tinge of rue. Barry later went on to call games for TBS and TNT.

Barry told me he never played basketball after retiring in 1980, save for some short stints during games at his camps. But he continued to crave competition. Barry turned his attention to long-drive tournaments in golf — he reckons his best was about 360 yards — and won four world championships in his age group.

He played a lot of tennis but by his early 70s felt that the sport was getting too hard on his body. Someone recommended pickleball. “What’s pickleball?” he remembers asking. Barry gave it a shot and “fell in love with it.” But merely playing recreational games at local courts wouldn’t cut it. “I thought, ‘OK, I’m going to get good enough to win a national championship [in his age group],’” he says. With his size, wingspan and the advanced hand-eye coordination of an elite athlete, he got very good very fast. And sure enough, Barry has won several championships at the national level. (For you pickleballers, he ranks himself a 4.5 — out of 5 — player.)

Barry is fortunate to be playing any sport these days. In July 2014, he suffered a horrific accident while cycling in Colorado Springs, fracturing his pelvis in six places. He was flown to a trauma center outside Denver, where Dr. Nimesh Patel performed a six-hour surgery. Barry has an Erector Set’s worth of rods, pins and screws in his right hip area. (I can attest; he texted me an X-ray.) “I thank God every day for Dr. Patel,” Barry gushes. “After the surgery, he said, ‘Rick, if you had the bones of a man your age, I could never have operated on you.’”

Barry spent three months in a wheelchair and several weeks at a rehab facility in Colorado Springs. Early on, he joined a physical therapy class with some elderly folks. Their wheelchairs formed a circle and they started passing a light ball between them. The hoops Hall of Famer wasn’t having it. “I talked to the lady that was running it,” Barry recalls, “and I said, ‘Excuse me, I think I can throw and catch a ball. This is not working for me. I need rehab so that I can get out and have my life back.’”

Barry says he was up and functioning well in about six months. He’s deeply grateful for his return to form. “I’m a Type A personality,” he says. “For me not to be active would be, like — my God, I can’t imagine it.”